Header photo courtesy of Marlin Harms.

Are bird populations that depend on the bay and surrounding lands stable?

Yes, the diversity of birds in the Morro Bay area appears stable, but some types of birds face difficult conditions or are changing their behavior due to forces such as climate change and habitat loss.

The Morro Bay estuary and watershed provide a variety of habitats that support a wide diversity of bird species. Understanding the health of bird populations is a crucial tool for tracking environmental health. Across the country, a third of U.S. birds need conservation action for protection, which safeguards both habitats and the economy. About 100 million Americans are birdwatchers, with bird-related expenditures reaching approximately $100 billion in 2022.

The 2025 State of the Birds report produced by the North American Bird Conservation Initiative (NABCI) cites a loss of three billion North American birds in the past 50 years. While some groups of birds are faring better than others, loss of habitat and declining populations put all birds at risk. One of the best strategies for reversing the current trend is to research species-specific declines to better understand what causes them and enact informed conservation measures. In the sections below, we highlight projects that are actively collecting valuable data on bird populations to aid in their management and recovery.

Snowy Plover Populations on the Morro Bay Sandspit

The western snowy plover is a small shorebird that nests directly on the sand. In 1993, the federal government determined that this species required additional protection and management to improve its chance of survival. Plover nests are vulnerable to trampling, habitat loss, and being eaten by predators. California State Parks is responsible for managing plover habitat in the San Luis Obispo Coast District, which stretches from north of San Simeon to the southern end of the sandspit. State Parks plover management consists of maintaining eight miles of symbolic fencing around nesting areas, monitoring predators, and increasing survey efforts during the breeding season (March to September).

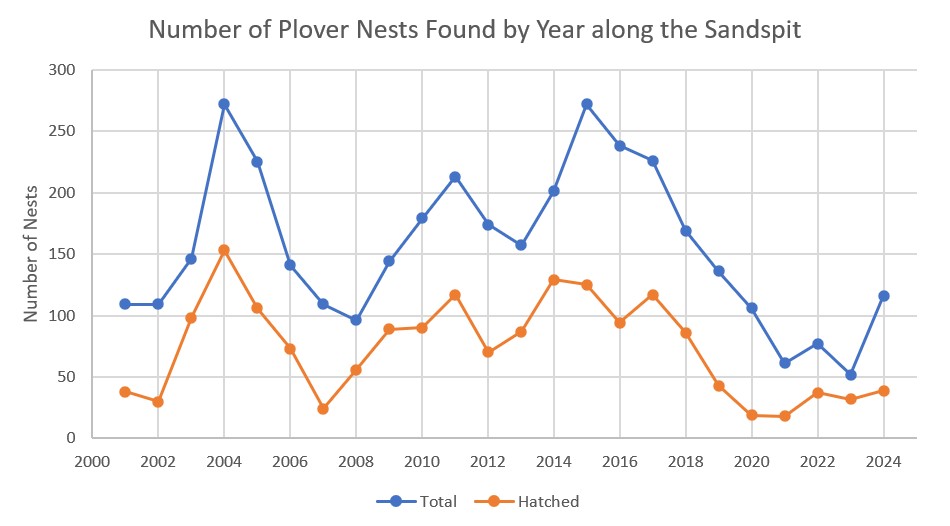

The portion of the Sandspit owned by State Parks has the highest density of plovers in the San Luis Coast District and typically reflects trends from across the region. The number of plover nests found on the sandspit during breeding season surveys has been declining since 2015, however a recent uptick in 2024 resulted in the highest number of plover nests observed in the past five years.

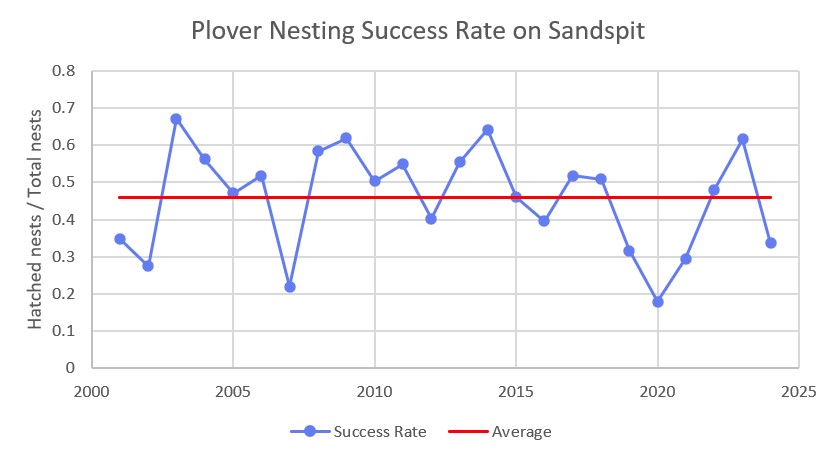

Despite the increase in total nests, the number of nests resulting in successfully hatched plovers has been relatively stagnant since 2019. On average, just under half of plover nests on the sandspit are successful. Only 34% hatched in 2024, which follows two years of higher-than-average nest success. The main culprit for nest failure on the sandspit is predation by coyotes.

Even though the road to recovery for the western snowy plover has been long and challenging, the trend across Recovery Unit 5 (the broader area that includes the San Luis Coast District) is reporting a gradual, positive trend in plover numbers, which would not be possible without the management actions and stewardship of State Parks and other partners.

Black Brant Migration Shifts

These small stocky geese are a familiar sight in Morro Bay in late fall to early spring. Black brant are a migratory species, stopping by Morro Bay on their way to Mexico to escape the bitter cold of winter on the Alaskan tundra. They migrate along the Pacific Flyway, which is the north-south corridor for bird migration in the Americas that is over 4,000 miles long and up to 1,000 miles wide.

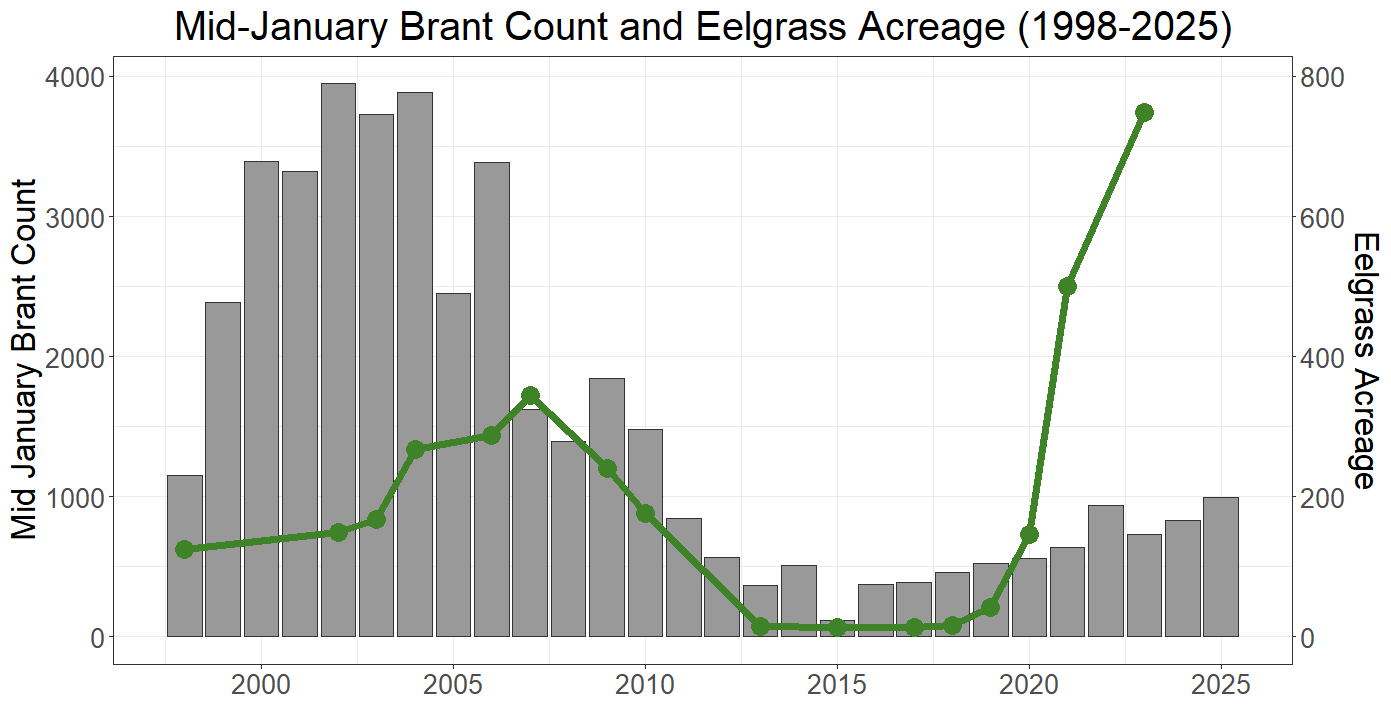

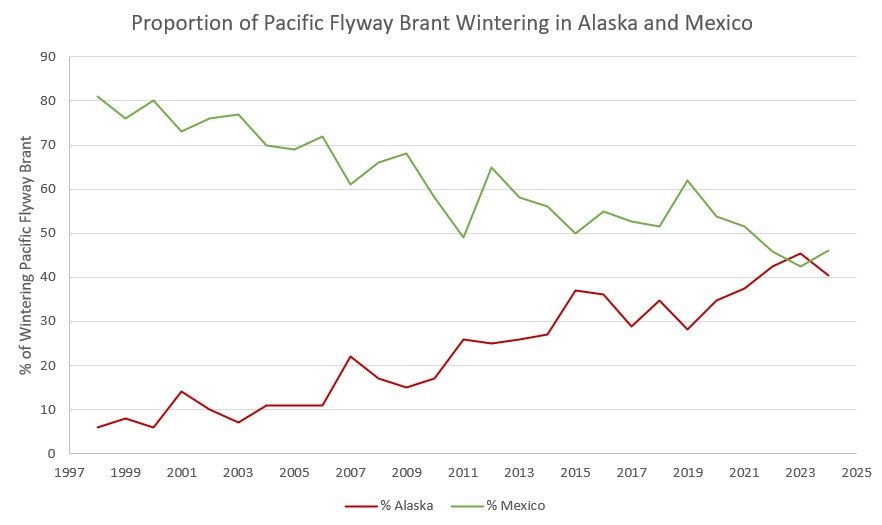

In the past, the number of black brant in the Morro Bay estuary has fluctuated along with changes in eelgrass acreage, since it serves as an important food source for these birds. During the most recent eelgrass decline period from 2007 through 2015, brant populations also decreased. Even though eelgrass has made a significant comeback in the past few years, the Morro Bay brant population has not rebounded to the same degree. This decline in the Morro Bay brant population is due at least in part to a shift in temperature. As the Alaskan Peninsula continues to experience warmer winters, more brant are opting to skip the arduous 4,000-mile journey to warmer climes and instead remain in Alaska for the winter. This means fewer brant are stopping by Morro Bay to forage on eelgrass.

Fortunately for brant, the decline observed in our local population is not reflective of the population along the entirety of the Pacific Flyway. The Pacific Flyway population has remained relatively stable, meaning that the change in migration pattern has not yet impacted the brant population as a whole. For more information on brant migration, and trends of other migratory birds from around the world, check out eBird’s weekly abundance maps.

Monitoring Los Osos Bird Populations

In addition to the surveys tracking shorebirds within the estuary, the Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) program is actively monitoring the demographics of land birds at a site in Los Osos. This local site is but one of approximately 300 active stations from across North America collecting valuable, long-term datasets according to a standardized protocol developed by The Institute for Bird Populations.

The Los Osos bird-banding station began surveying the passerine bird population (commonly referred to as the “perching birds”) in 2006, situated on a piece of State Park land that includes both Baywood fine sand and coastal scrub habitat types. During their annual surveys conducted between May and August, a team of trained volunteers, students, and permitted bird banders set up mist nets throughout the site to safely catch birds for data collection. The temporarily captured birds are then assigned a species identification, age class, sex, and breeding condition based on established protocols before being carefully banded and released. As of 2009, feather collection for the Bird Genoscape Project has added a new dimension to this monitoring program, allowing for the sequencing of genetic markers to characterize migratory patterns and population connectivity. This brief overview represents only a fraction of the data recorded by the MAPS team, all of which can be used to inform conservation efforts.

From the Los Osos station’s 2024 survey results, Song Sparrows and Wilson’s Warblers were the most abundant, collectively making up over a third of the birds captured and released. Wilson’s Warblers are unexpectedly successful at the Los Osos site, amidst the backdrop of a declining population throughout most of their range. The Coastal California population of Wilson’s Warblers, representing the majority of those seen at the Los Osos site, has been identified as genetically distinct and highly vulnerable to local extinction by analyzing data from the Bird Genoscape Project (Ruegg et al. 2020). This case study highlights the importance of the collaborative aspect of the MAPS project, which brings together numerous partner organizations throughout the continent to better understand bird population dynamics and prioritize the conservation of at-risk species.

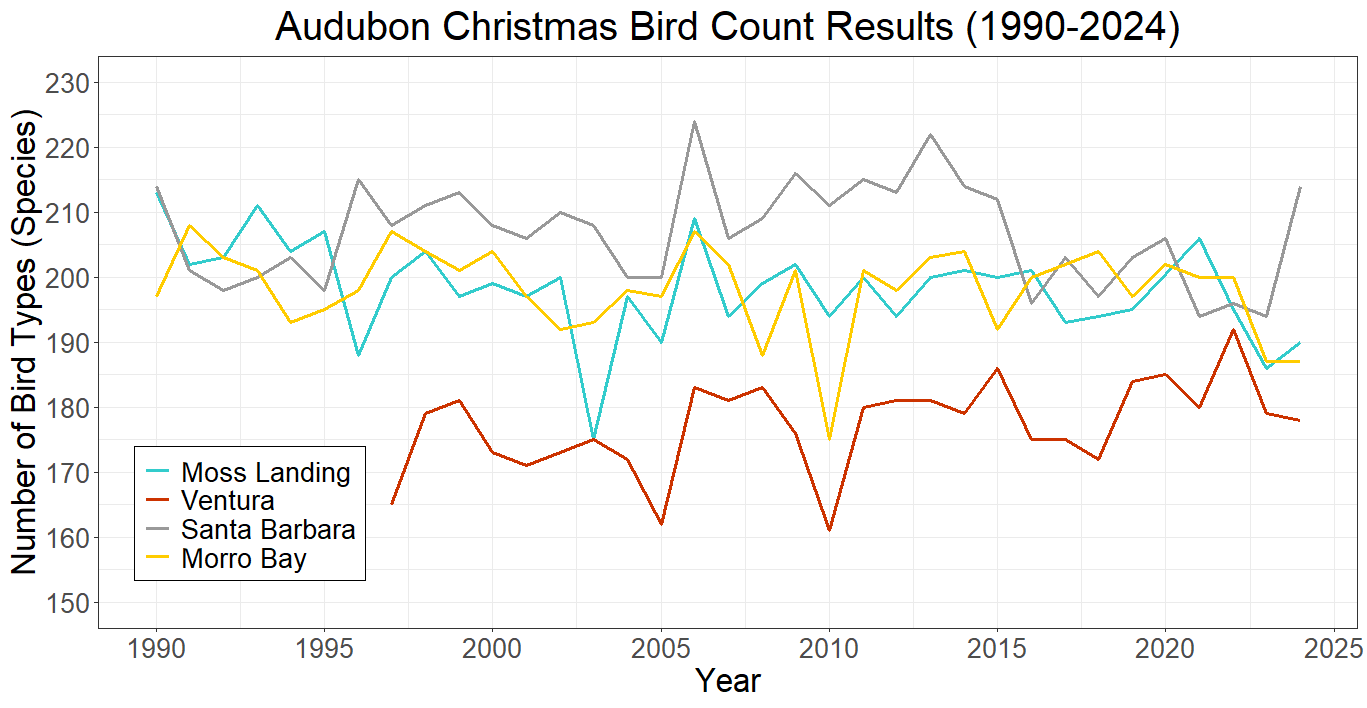

Community Science in Action: Audubon Christmas Bird Count

Each December, the National Audubon Society hosts a Christmas Bird Count event. Birders across the nation gather to count birds in their local area as part of the longest-running community science bird project in the United States.

Locally, the count is organized by Morro Coast Audubon Society. The 2024 Morro Bay Christmas Bird Count was held on Saturday, December 14 and was conducted within a 15-mile diameter circle that encompassed the estuary, much of the watershed, and areas north of Morro Rock along the strand. The count recorded 187 species, which is slightly below the average count for data going back to 1980. Over 43,000 birds were counted, which is near the average of counts since 1980. Since the start of surveys in 1948, 323 unique species have been recorded, with the addition of two new species during the 2024 count (Least Bittern and Leach’s Storm Petrel). For full details on the survey and to see trends in the data from our area and beyond, visit the Audubon Christmas Bird Count website.

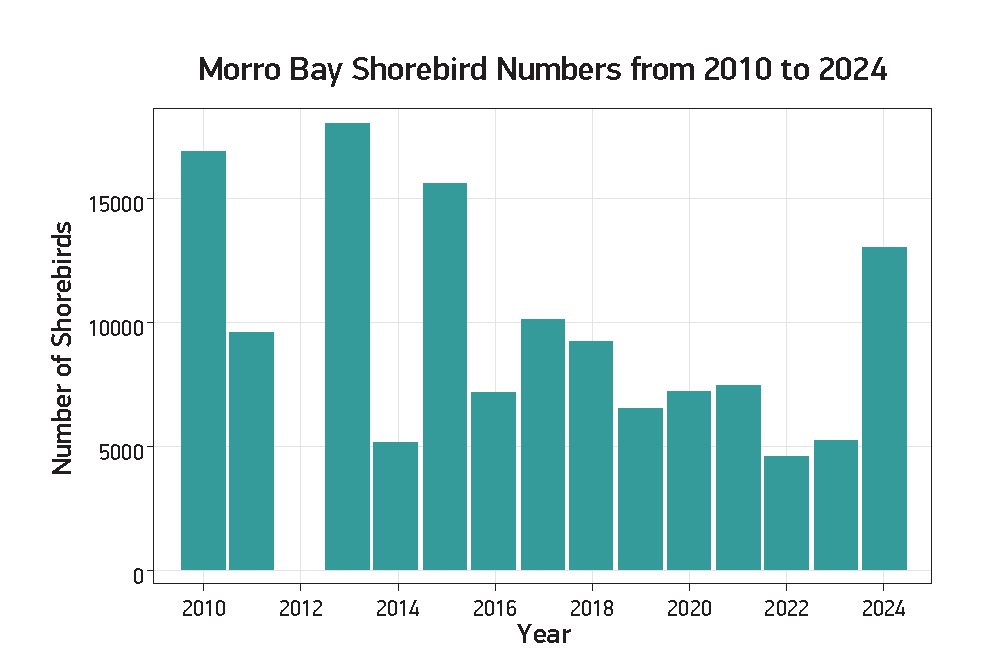

Tracking Our Shorebirds

Since 1988, Point Blue Conservation Science and the Morro Coast Audubon Society have conducted annual surveys to track overwintering shorebird populations within the estuary, along the sandspit, and across Morro strand. During the survey, a few dozen volunteers venture out into the estuary by foot and by kayak to pre-defined survey areas, where they are close enough to observe birds through a spotting scope but can maintain adequate distance to avoid disturbing them. The volunteers then identify and count all shorebirds that use the survey area, record the current weather conditions, and make note of important habitat characteristics. Their combined efforts result in a reasonably complete census of overwintering shorebird populations.

Since 2010, Morro Bay’s survey results have been part of a broader study called the Pacific Flyway Shorebird Survey (PFSS), which partners with the Migratory Shorebird Project (MSP) to monitor shorebird populations across the Pacific Flyway from Chile to Canada. By monitoring shorebirds at their wintering areas in thirteen countries each year, this collaborative project generates species-level population trends for the Pacific Flyway to guide management and conservation efforts. To view shorebird composition and abundance in greater detail, you can use the interactive map on our State of the Bay dashboard.

Data Notes

National bird conservation statistics come from the North American Bird Conservation Initiative’s (NABCI) 2025 State of the Birds Report. Morro Bay shorebird surveys follow methods outlined in Reiter et al. 2020. The shorebird abundance graph uses survey results provided by Point Blue Conservation Science. In this graph, no bar is present for 2012 because a survey was not conducted that year. Los Osos bird population data and trends were provided by the Powell II Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) Station. Bird banding at the Los Osos station is conducted in collaboration with the Institute for Bird Populations, California Central Coast Joint Venture, and is facilitated by the California State Parks San Luis Obispo Coast District.

References

Audubon Christmas bird count: Morro Bay and Carrizo Plain Christmas Bird Counts ~ Morro Coast Audubon Society

California State Parks. 2024 Annual Report for the Western Snowy Plover at San Luis Obispo Coast District. January 30, 2025.

Local brant data is collected by John Roser, local biologist and citizen scientist, using standardized methods.

Information about brant migration patterns is based on U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service data: pacific-flyway-data-book-2024

North American Bird Conservation Initiative (NABCI) 2025 State of the Birds Report: State of the Birds 2025

Pacific Flyway Shorebird Survey Data from Point Blue: Pacific Flyway Shorebird Survey – Migratory Shorebird Project

Reiter, M. E., Palacios, E., Eusse-Gonzalez, D., Johnston, R., Davidson, P., Bradley, D. W., Clay, R., Strum, K. M., Chu, J., Barbaree, B. A., Hickey, C. M., Lank, D. B., Drever, M., Ydenberg, R. C., Butler, R. 2020. A monitoring framework for assessing threats to nonbreeding shorebirds on the Pacific Coast of the Americas. Avian Conservation and Ecology. 15(2):7. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-01620-150207

Area-Search Protocol for Surveying Shorebirds in Coastal Environments

https://migratoryshorebirdproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/AreaSearchProtocol_Coast_2017.pdf

Monitoring Avian Survivorship and Productivity (MAPS) Program 2024 Annual Report: 2024 Annual Report

Ruegg, K. C., Harrigan, R. J., Saracco, J. F., Smith, T. B., Taylor, C. M. 2020. A genoscape-network model for conservation prioritization in a migratory bird. Conservation Biology. 34(6) https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fcobi.13536