Header photo courtesy of Christa Renee.

Is the bay clean enough to support commercial shellfish farming?

Yes, in active harvesting areas.

The tranquil waters of the Morro Bay estuary support a thriving aquaculture industry. The Morro Bay Oyster Company and Grassy Bar Oyster Company provide Pacific oysters to restaurants and grocery stores locally and beyond. Oysters spend about 12 to 18 months in the waters of Morro Bay before reaching market size. The California Department of Public Health oversees testing to ensure that the shellfish growing waters remain clean and safe.

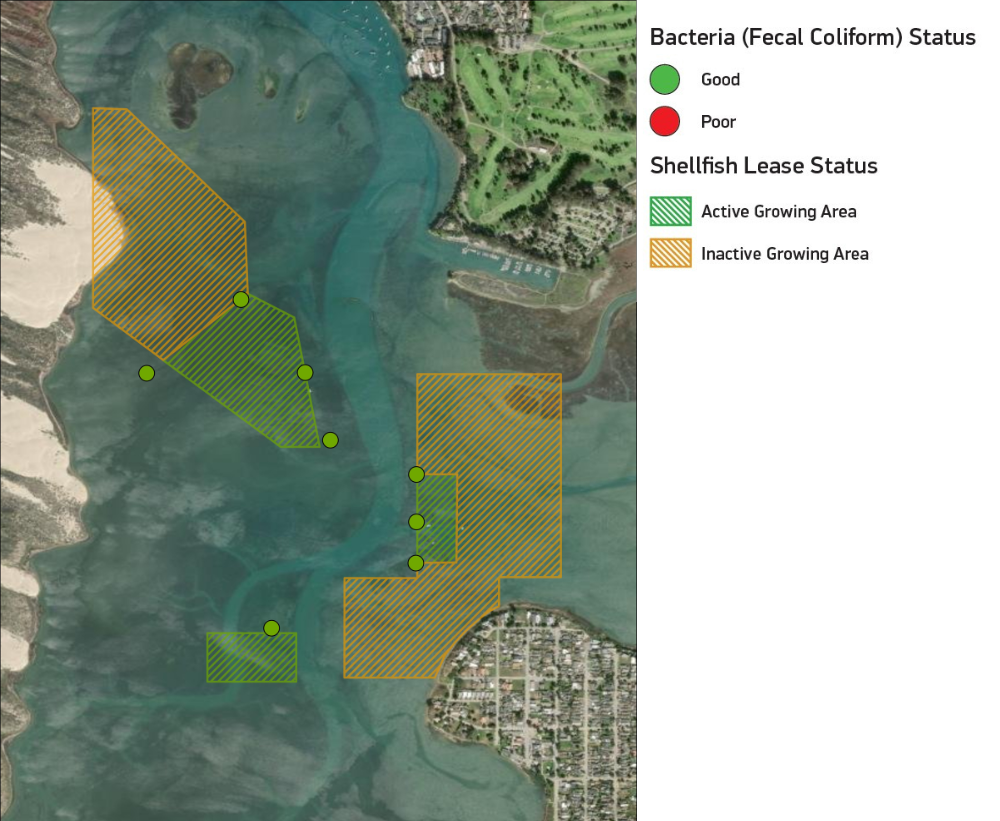

The crosshatched portions of the map below illustrate the lease areas where shellfish farming could potentially occur. Areas shown in green undergo water quality testing for bacteria to determine if the waters are clean enough for shellfish harvesting. All active shellfish farming operations occur within these areas. Orange areas indicate either historically poor water quality or insufficient data to assess conditions.

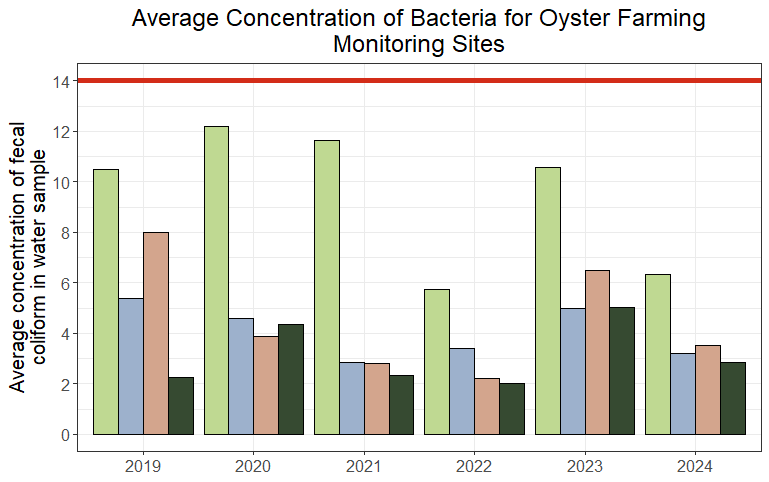

Water Quality Data by Year

Life on an Oyster Farm

The History of the Oyster in Morro Bay

The oyster industry in California began with the Gold Rush. This influx of easterners wanted familiar foods, including the eastern oyster. Native oysters, with their darker meat and strong coppery flavor, did not appeal to eastern palettes. Initially, oysters were shipped to California by boat from Washington state. With the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, fresh eastern oysters could reach the West Coast in three weeks. Oyster seed was also sent west, where it was raised to harvestable size, often in San Francisco Bay.

In 1910, the industry began declining in San Francisco, likely due to increasing industrial pollution and changing economics. In 1930, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife introduced the Pacific oyster from Japan. Pacific oysters far out-competed both the native Olympia oyster and the eastern oyster due to their lower production costs and mortality rates.

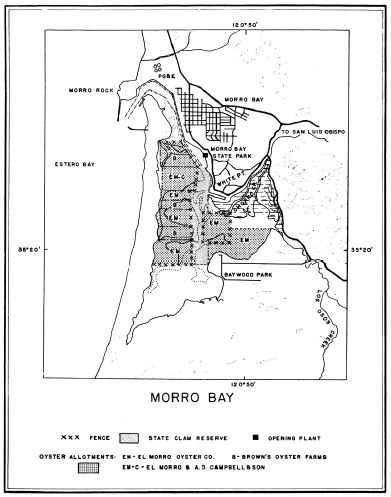

By 1935, over 70% of 2,300-acre Morro Bay was allotted for oyster growing. Farmers scattered seed oysters from boats when the beds were underwater and harvested them by hand at low tide after about two years of growth.

When trade with Japan was cut off during World War II, Morro Bay obtained seed from Washington state and became the leading oyster producing area in California. In 1964, Morro Bay’s production peaked at nearly 250,000 pounds of oysters harvested during the year. At that time, oysters were sold shucked in jars. Today, consumers prefer their oysters whole in the shell. There are currently 75 acres available for oyster farming, which is only 3% of the bay’s acreage.

Shellfish Research and Restorative Aquaculture

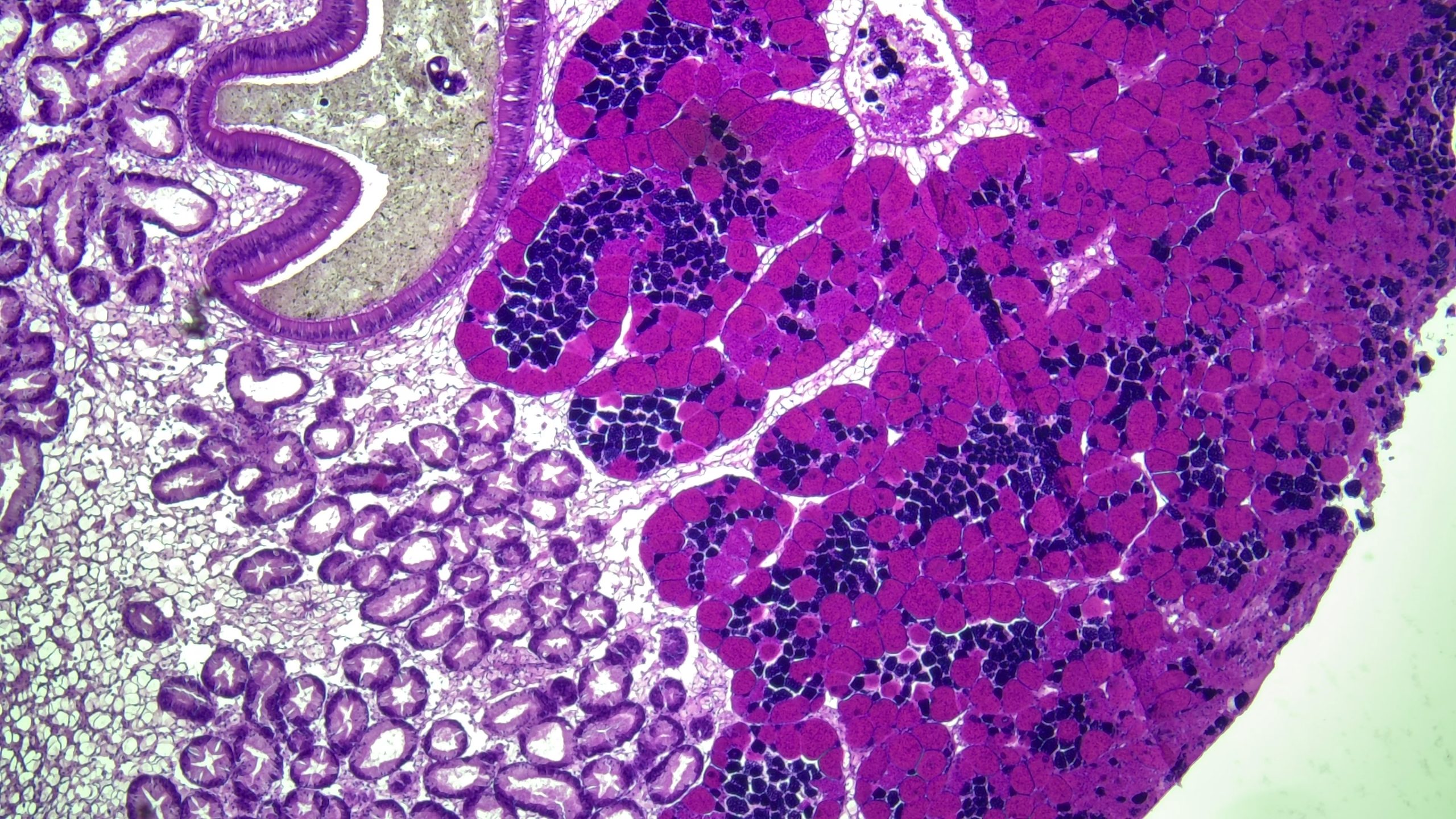

Dr. Kevin Johnson, California Sea Grant Aquaculture Extension Specialist and research scientist for Cal Poly’s Biological Sciences Department, leads a research lab focused on shellfish aquaculture in California. In his lab, a team of graduate and undergraduate student researchers use field studies, laboratory experiments, and genetic sequencing to improve our understanding of local shellfish and improve their survival in the face of ever-increasing environmental stressors. As part of this work, shellfish growers from Morro Bay, Northern California, and Washington send a portion of their Pacific oyster stock to Dr. Johnson’s lab each month so they can study how different lineages differ in growth rate, survivorship, and “meat weight” across four estuaries actively culturing oysters. These metrics help the oyster farmers track the development of different oyster strains and determine if there are trends that can be used for oyster hatcheries to increase yields across the U.S. West Coast.

In addition to Pacific oysters, which have been a staple of California’s aquaculture industry for decades, the lab has partnered with The Nature Conservancy in California to explore the potential for restorative aquaculture of native shellfish species. Olympia oysters are the only oyster species native to the West Coast of North America, and some populations have experienced a 99% decline compared to their historic abundance. To support their restoration, graduate students in Dr. Johnson’s lab are deploying bags of Olympia oysters at Morro Bay’s local shellfish farms to study how they respond to stressful conditions and to watch for evidence of reproduction and recruitment throughout the bay. The goal is to see the Olympia oyster population recover while also allowing commercial production of the species. In addition, the lab is using genomic approaches to further conservation goals throughout the state. Through a combination of whole genome sequencing and comparative transcriptomic analyses, the team is looking to identify populations of native oysters more resilient to temperature and oxygen stress. This information can help guide breeding strategies to support Olympia oyster restoration throughout the state.

Finally, in collaboration with Professor Kristin Hardy at Cal Poly, Dr. Johnson’s lab is conducting research in Morro Bay on the Pacific littleneck clam, a species native to California. Currently, the non-native Manila clam dominates California clam aquaculture, but many growers are looking to the cultivation of native species as a sustainable strategy for reducing the threat of disease outbreaks, which are an ongoing issue. Along with a commercial benefit for the aquaculture industry, adding Pacific littleneck clams and Olympia oysters to shellfish farms benefits the local environment. Cultivating native shellfish species restores the ecosystem services they provide, such as nutrient removal and turbidity reduction, which help keep the estuarine habitat clean and healthy. In addition, by using the local genotypes for commercial cultivation it is possible to passively help increase the size of the wild populations as these species can successfully reproduce and recruit in Morro Bay.

Harmful Algal Bloom Monitoring

Dr. Alexis Pasulka of Cal Poly’s Biological Sciences Department works with the Estuary Program and our volunteers to collect bay water samples for phytoplankton identification and genetic analysis. Dr. Pasulka’s research seeks to improve understanding of the factors driving harmful algal blooms (HAB) to better predict the appearance of plankton species that can impact shellfish farms.

Preliminary results show that HABs follow seasonal patterns within the bay that are similar to the surrounding coastline, however differences in environmental conditions between the front bay and back bay contribute to differences in the phytoplankton community composition. By continuing to explore these patterns, this project will develop a better understanding of the driving factors behind toxic blooms and aid in the prediction of future HAB events. To learn more about the HAB-forming species monitored by this project and observe results from the first two years, visit the interactive dashboard here.

Data Notes

Data and updates to the lease areas in the map were provided by the CA Department of Public Health. The bacteria data from 2019 through 2024 was analyzed for the geometric mean of the fecal coliform concentration.

References

BuyanUrt, Buyanzaya. Effects of Temperature and Oxygen Stress on Two Populations of Olympia Oysters (Ostrea lurida) from Central California. Cal Poly Digital Commons. https://digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/theses/3179/

California Sea Grant. Project R/SFA-18: “Evaluating the potential for commercial aquaculture of the native Pacific littleneck clam (Leukoma staminea) in Morro Bay estuary, CA.” https://caseagrant.ucsd.edu/our-work/research-projects/evaluating-potential-commercial-aquaculture-native-pacific-littleneck

History of oyster farming in California: https://escholarship.org/content/qt1870g57m/qt1870g57m.pdf

Upholt, Boyce. “Good Data, Unexpected Solutions”. California Sea Grant. https://caseagrant.ucsd.edu/news/good-data-unexpected-solutions

University of Connecticut (UConn) Extension’s overview of Floating Upweller Systems (FLUPSYs): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SQ6q8H5_VjI