Do the estuary and watershed support a healthy population of steelhead?

No, the local steelhead population continues to be threatened even with some habitat improvement.

Steelhead are a migratory species of fish that are native to the Morro Bay watershed. Steelhead are considered great indicators of stream health since they require cold, clean water, and complex habitat to survive. While once abundant along the Central Coast, steelhead are now federally listed as a threatened species. Without further protection, they are likely to become endangered within the foreseeable future. The Estuary Program prioritizes projects that benefit steelhead due to their ecological significance and their status as a threatened species.

Steelhead Life Cycle

Managing Invasive Predators

One of the many threats facing steelhead in the watershed is an invasive species of fish called the Sacramento pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus grandis). Despite their unassuming name, adult pikeminnow can be ravenous predators that consume juvenile steelhead and compete with them for food and habitat. The Estuary Program partnered with Stillwater Sciences to manage invasive pikeminnow in the watershed beginning in 2017. Since then, over 800 pikeminnow have been removed from Chorro Creek.

Finding Refuge in Cool Water

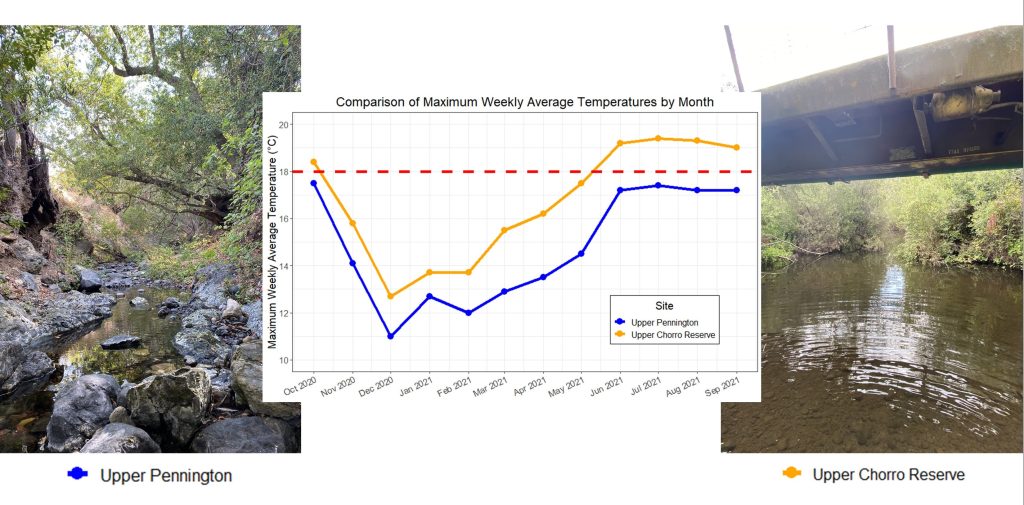

Deep shaded pools provide the cool, well-oxygenated water that steelhead rely on for survival during the summer and fall. The Estuary Program uses a network of continuous water temperature loggers for data collection to determine ideal locations for steelhead. These small, reliable temperature loggers are typically submerged in deep pools and attached with cables to anchors like trees or roots. We can download data from these loggers in the field using a simple Bluetooth connection and a cellphone.

While steelhead may tolerate warm temperatures for short periods of time, they are sensitive to prolonged elevated temperatures. Steelhead trout need a temperature range of about 13 to 18°C, or 56 to 64°F, in order to spawn. If the temperature exceeds this level for extended periods of time, steelhead can experience physiological stress. This can affect their ability to survive and reproduce. The Estuary Program uses the maximum weekly average temperature to determine the warmest temperature in a seven-day average. This helps us identify times of year when temperatures are too high for too long to support a healthy population of steelhead.

This graph shows maximum weekly average temperatures during 2021 at two locations. The orange line shows temperatures at a site along the mainstem of Chorro Creek, which tends to be warmer than ideal for steelhead. The blue line shows temperatures on Pennington Creek, a smaller creek that drains to Chorro Creek that tends to have cooler waters and more optimal steelhead habitat. The red-dashed line shows a temperature threshold of 18°C, or about 64°F. Temperatures below the red-dashed line are more favorable for steelhead than those temperatures that are above it. Pennington Creek was able to maintain temperatures year-round that were favorable for steelhead, while Chorro Creek experienced higher than desirable temperatures throughout the summer.

Barriers to Migration

Whether it’s the pursuit of cold water, food, or spawning habitat, migratory movement is key to the survival of steelhead and rainbow trout. Ocean-going steelhead migrate from freshwater streams to the ocean and back. While resident rainbow trout do not make the journey to the ocean, they may depend on seasonal migrations within the watershed to survive.

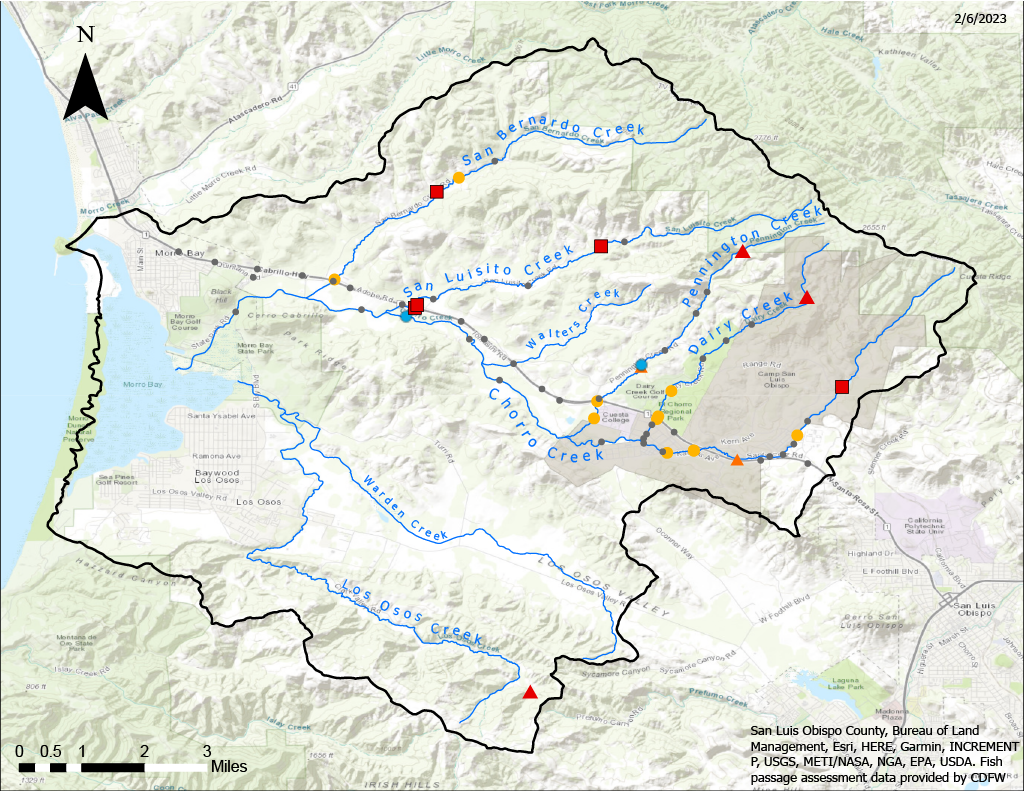

A fish passage barrier is an obstruction that impedes fish migration. Barriers include both natural and non-natural features. Natural barriers like waterfalls and non-natural barriers like dams or culverts may block the passage of fish, threatening their historic migration patterns. Some barriers only limit fish passage during certain flow conditions or for specific sizes of fish such as smaller juveniles. Others may inhibit passage under all flow conditions for all life stages. Addressing these barriers is a high priority for the Estuary Program and our partners to restore habitat for steelhead.

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) maintains an active database of known and potential fish barriers in California called the Passage Assessment Database (PAD). This database serves as a standardized location for fish barrier assessment information in the state and consists of data compiled from hundreds of organizations, including the Estuary Program.

The map shows current and remediated fish migration barriers within the Morro Bay watershed. Red triangles indicate natural barriers like waterfalls, which fish cannot migrate past at any time of the year. Orange triangles indicate natural partial barriers which fish may be able to pass during certain flow conditions. Orange circles indicate unnatural partial fish barriers. Blue circles indicate barriers that have been remediated to allow fish passage year-round. Red squares indicate non-natural total fish barriers, like from a culvert or dam. Those in grey indicate an unknown fish passage status. Data was retrieved from CDFW’s Passage Assessment Database (PAD) in February 2023. Data is subject to change.

For more information on the PAD, or to see all barriers in California, you can visit the PAD Map Viewer.

How Much Water is Enough?

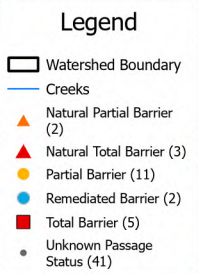

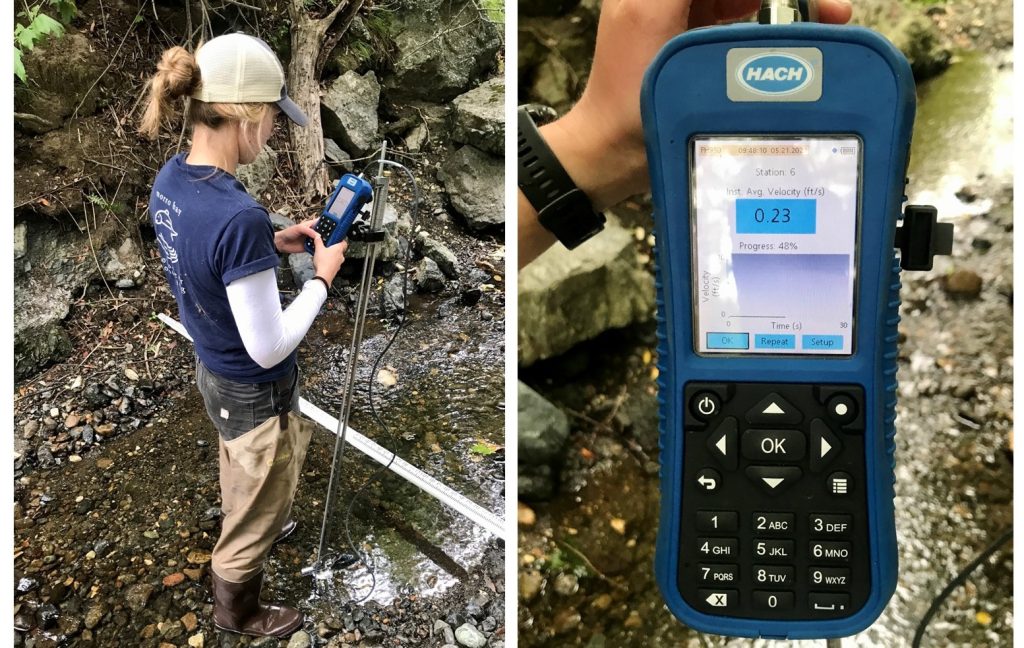

Water availability and adequate stream flow are the key drivers of a healthy aquatic ecosystem. Adequate flows in the spring and summer are especially important for steelhead, since fish migrate in the spring and temperatures are warmest in the summer. The Estuary Program recently launched an expanded monitoring effort to better understand spring and summer low flow conditions in the watershed.

During the spring and summer, volunteers and staff visit nine sites every other week to measure flows. Our teams utilize specialized equipment to collect stream flow measurements. We measure how much water is in our creeks using a method called the “velocity-area method.” This technique uses water width, depth, and velocity to estimate the stream flow rate in cubic feet per second.

Tracking Water Levels

While manual stream flow measurements are extremely valuable, they can only capture flow rates at a specific moment in time. In order to capture a wider set of conditions, the Estuary Program maintains water level gauges throughout the watershed. The gauges collect water depth measurements every 15 minutes, all year long. Using specialized equations, we then convert the water depth data into a stream flow rate. The result is a continuous stream flow dataset for each site year-round.

Data Notes

California Fish Passage Assessment Database (PAD): https://www.calfish.org/ProgramsData/HabitatandBarriers/CaliforniaFishPassageAssessmentDatabase.aspx

Continuous water temperature monitoring blog: https://www.mbnep.org/2020/10/02/continuous-water-temperature-monitoring-in-our-creeks/

Canet Road County Gauge information: https://wr.slocountywater.org/sensor/?site_id=41&site=093f8e0b-dfde-4a45-b291-174ce07ead12&device_id=3&device=8e787d49-7f71-41b1-ae12-2559889f3431

2020 Pikeminnow Suppression Report: https://www.mbnep.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/2020-Chorro-Creek-Pikeminnow-Suppression_Stillwater-1-1.pdf

Low flow monitoring blog: https://www.mbnep.org/2022/10/07/field-updates-september-2022-low-flow-monitoring/