Guest post by John Roser

John’s field biology work began about 35 years ago. Early field work was with California Condors and Bald Eagles. Eventually he detoured into an enjoyable 25-year career in outdoor science education. Over 20 years ago John began a voluntary study of Morro Bay’s wintering Brant Population. His interest in Brant has led him to volunteer with Brant biologists from Baja to Humboldt Bay and as far as Brant breeding colonies in arctic Alaska.

In the mid 1990s I often heard the opinion that one of Morro Bay’s icons, Black Brant geese, were in decline. Old-timers from the hunting, birding, and biology communities all had similar concerns. Sounded to me like there was potential for a valuable volunteer project. After consulting with flyway Brant biologists I began a personal project that focused on two goals: 1) to read enough bands on individually banded Brant to create a Morro Bay specific data set large enough for use in a diversity of flyway Brant studies and 2) to begin careful, long-term monitoring of Morro Bay’s wintering Brant population. That was 21 years ago.

Brant are fascinating. The subspecies seen in Morro Bay, Black Brant, breed along arctic coastlines from Russia to central Canada. They winter at coastal sites from Alaska to Baja and Sinaloa, Mexico. After breeding, Black Brant stage in the fall at Izembek Lagoon on the Alaska Peninsula. If traveling to Baja, these athletes can cover the 3,300 miles from Izembek to Bahia San Quintin in 54 hours—in a single nonstop flight!

Wild Black Brant have lived over 30 years and Brant pair for life. A pair will spend every day together throughout the year, even migrating side by side. After travelling thousands of miles, they often return to the exact same spot year after year to nest.

Once able to fly, Brant goslings follow their parents to fall staging and wintering areas, soaking up wisdom regarding the resources and dangers of an entire flyway; wisdom passed down through generations.

Multiple long-term Black Brant banding studies are ongoing. Brant are banded in arctic breeding areas from Canada to Russia. During the first five winters of my project I lugged around a large telescope and spied on Brant legs. I obtained several thousand band resightings and met my band reading goal.

The very first bands I was able to read happened to be bands on all five members of a family group. I saw them in early November, shortly after Brant arrive on Morro Bay, and I continued to see them through mid-April when most Brant have left. The five members of the family were always seen side by side. The next summer I spent a few weeks at a remote site in Alaska helping to band Brant.

It turned out that the parents of that family traditionally nested about 100 yards from my tent site—a fun coincidence.

Brant exhibit strong fidelity to their wintering sites, often returning to the same site year after year. I continued to see that pair and one of their kids for a few more years. I also had the pleasure of spotting many Brant over the years that I helped band that summer.

The wonderful diversity of bird life that passes through Morro Bay weaves a web across continents from pole to pole. My favorite Brant band sighting followed an impressive strand of that web. A few years ago I spotted a Black Brant in Baywood Cove wearing a strange, unfamiliar type of band. It turned out that a Russian ornithologist who was not studying Brant happened to capture a few while working on other species. He banded them to see if he would get lucky with resightings.

I was lucky enough to see one. That bird was from the Lena River Delta on the Laptev Sea almost half way across Asia, hundreds of miles west of established Russian Black Brant banding sites. The probable one-way route that bird took from the Lena River Delta to Morro Bay spanned 4,800 miles across two continents!

My second goal, monitoring Morro Bay’s wintering Brant, is ongoing. Brant use Morro Bay from November through April. Each year I create a seasonal use-day estimate to gauge the level of Brant use over the six-month season. If 100 Brant were on the bay for one day it would equal 100 Brant use-days. If they stayed a week it would be 700 use-days. I use an established protocol incorporating multiple baywide counts through the season to come up with the seasonal estimate.

Sixteen years ago, my seasonal estimate approached 500,000 Brant use-days. It has steadily dropped since then. The last five years it’s been running around 50,000, down 90% from that half-million number. How do these numbers compare to the memories of the old-timers?

There are no historic use-day estimates for Morro Bay, however, I found two good, historic data sets of mid-winter counts specific to Morro Bay that can be looked at in relation to comparable mid-winter counts for the last 20 years. Between 1931 and 1942 Morro Bay mid-winter counts averaged close to 7,000 with a high count of over 11,000. From 1950 through 1966 counts averaged 6,000 with a high of almost 12,000. The last 20 years of comparable mid-winter counts averaged 1,500 with a high of 4,600. If just the last 5 years are examined, the average is only 350 with a high of 600. Not good.

It looks like the old-timers were correct in the mid 1990s. At that point, Brant numbers on Morro Bay were probably down from previous decades. They certainly have been way down for the last 20 years. A population trend at one small part in the flyway can be easy to detect but complicated to explain, especially for such a mobile species. Factors influencing Morro Bay’s Brant population can originate locally or thousands of miles away. The current Brant decline at Morro Bay can be linked to both local and global changes.

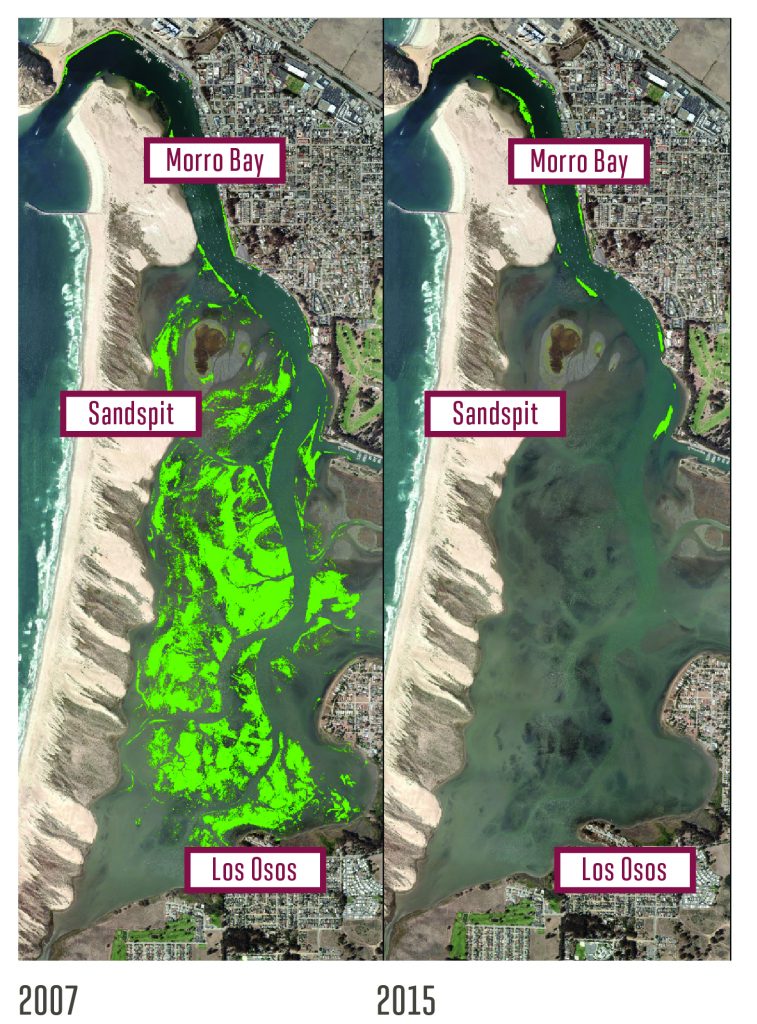

Eelgrass is the favored food of wintering Brant. Locally, Morro Bay’s Eelgrass beds declined from 344 acres in 2007 to 15 acres in 2013 and have remained near that level since then. The cause of the Eelgrass decline is not well understood, however, it’s reasonable to assume that a 95% drop in the primary food for Brant will take a large toll on the number of Brant supported by the bay.

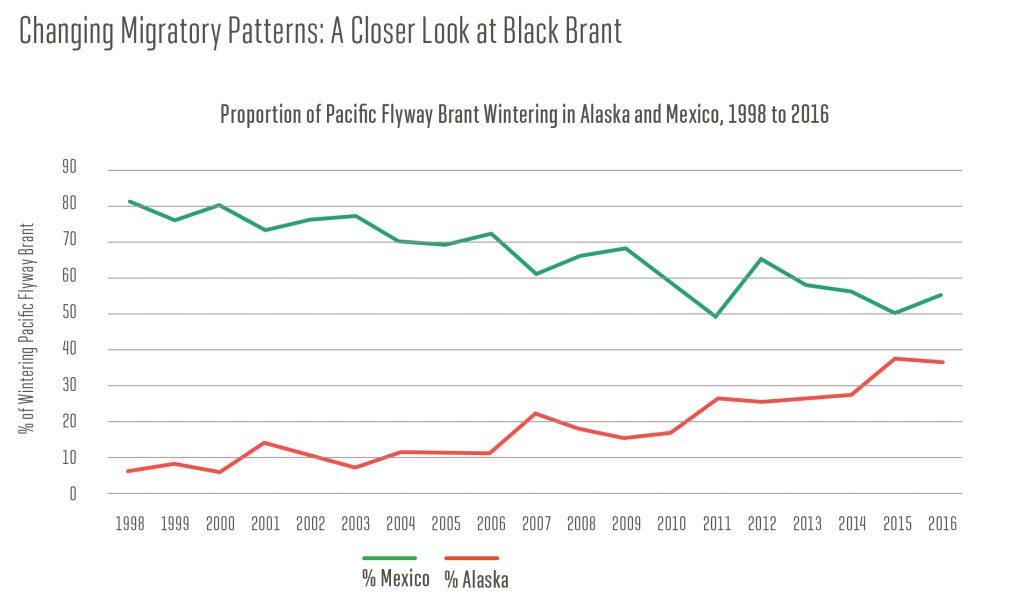

Global climate change is warming the northern reaches of the Pacific Flyway faster than the south with the most dramatic change occurring in the arctic. For a Brant wintering in Alaska warmer temps mean reduced calorie demands and greater Eelgrass availability due to less ice. When I began monitoring Morro Bay’s Brant 21 years ago about 6% of the flyway population of Black Brant wintered in Alaska and 85% wintered in Mexico. Those proportions are rapidly shifting. Lately about 36% of the population has been wintering in Alaska and as few as 50% have wintered in Mexico.

Surely this northward population shift should be factored into Morro Bay’s recent Brant decline.

I like to link Brant to the phrase ‘Think globally, act locally.’ A robust wintering Brant population needs abundant Eelgrass beds. Eelgrass needs a healthy bay and watershed. Our actions as stewards of the Morro Bay estuary and its environs truly do reverberate across our globe.