This is the third post to our blog series, Be Sea Otter Savvy, written by Gena Bentall, Director and Senior Scientist at Sea Otter Savvy. Posts in this series include tips on how to help sea otters thrive and information about sea otters’ behavior, biology, and their role in the estuary and ocean ecosystems.

When I was a little girl holding my mom’s hand on the shore in Pacific Grove in 1970, looking out at two sea otters rising and falling on a gentle swell, I knew them only from their faces in books. I knew nothing of the heroic acts of sea otter mothers, nothing of their metabolism, or their esteemed status as keystone predators. I only knew how I loved their beautiful faces. To see them come to life in this wild place where they seemed so at home was a gift beyond compare to that seven-year-old girl. Even then, I knew they belonged.

For five-million years, the sea otters’ survival equation has demanded to be balanced: the sea is cold, your body is warm, how will you survive? For the sea otter and the invertebrates of the north Pacific coast, an arms race has played out for millennia—an evolutionary battle waged long before humans arrived and changed the rules. In this age-old struggle for survival, the kelp grows toward the sun─breathing in CO2 and exhaling oxygen, the sea urchin grazes warily on its blades and stalks, and the sea otter hunts day and night to stoke the metabolic furnace that keeps the cold at bay.

That furnace is insulated by the densest fur of all. That fur inspired such covetous obsession that all thought of the wondrous inhabitant of the pelt was forgotten until extinction was all but inevitable. It is not without irony that it took the near loss of sea otters in the murderous eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to set up a massive ecological experiment that would change our understanding of their role in coastal ecosystems forever.

Any discussion of the ecology of sea otters begins and ends with one fundamental challenge: maintaining a warm mammalian body in a cold ocean. The incoming freshmen to the class of marine mammals, sea otters are the most recent among them to reenter the marine environment, returning to the ocean just five-million years ago. They lack some of the adaptations to ocean life of whales, dolphins, seals (who have lived in the ocean for thirty to fifty million years)—most notably, a blubber layer to act as insulation and energy storage—and so, must rely on that coveted fur coat and a hot furnace of a metabolism to maintain a stable body temperature. The digestion of food is the fuel for the furnace, and it drives their infamous appetite. A sixty-pound adult male sea otter will need to consume 3,500–4,300 (kilo)calories each day in the form of benthic invertebrates like urchins, crabs, clams, worms, and snails to survive.

Unlike their close cousins the river otters, sea otters do not rely on speed and sharp, grasping teeth to capture prey. They forage on the sea floor—feeling, digging, reaching with their forepaws—to acquire prey from a diverse array of species. If the sixty-pound male were feeding exclusively on urchins, he would have to find and consume more than 200 each day just to meet his energetic requirements. The more active he is—patrolling territory, traveling, or avoiding humans—the more urchins he will need to eat. This appetite exerts a powerful pressure on prey species, one that can create a “downstream” effect on other species in the coastal food web. This effect, flowing from the top of a food chain to the bottom, is known as a trophic cascade.

In an ironic twist of fate for the sea otter, the human hunger for their pelts left a decimated and fragmented population, which set the stage for the large-scale studies that would unlock the secret of their pivotal role in kelp forest ecosystems. On the windswept backbone of the Pacific on the Aleutian Islands chain in the 1970s, Dr. James Estes, then a graduate student, uncovered a story of sea otters and kelp forest that could only be revealed in the wake of near extinction.

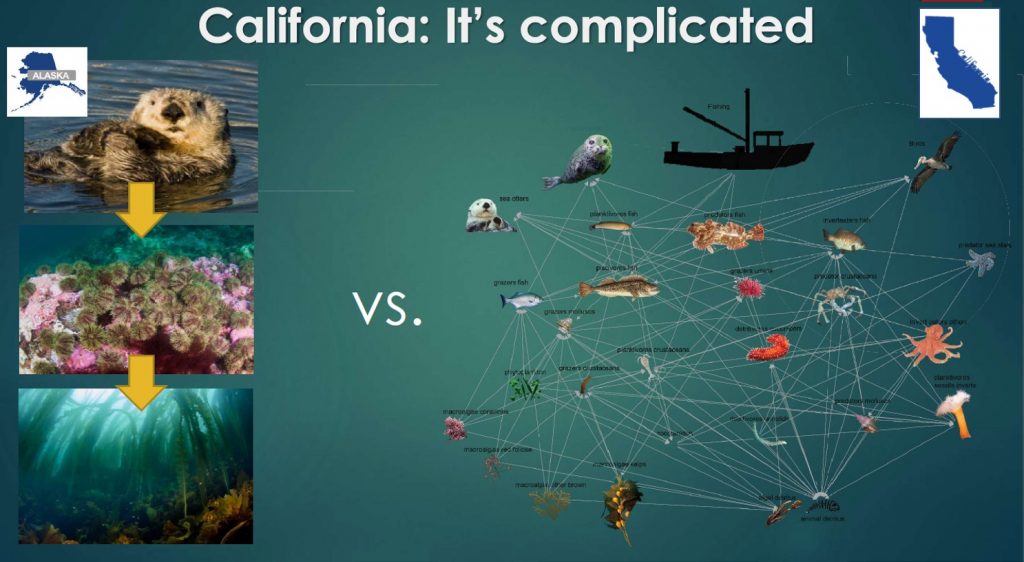

While this northern archipelago may seem too remote to have suffered human impacts, the fur trade left some of its islands devoid of sea otters, while others still cradled precious remnant populations. By comparing the near-shore ecosystems that surrounded islands with and without sea otters, Estes was able to show that the appetite of sea otters, by keeping numbers of the kelp-grazing sea urchins in check, allowed kelp forests (and the myriad of species depending on them) to flourish. Like the central stone, or keystone, at the top of a stone archway, sea otters held this ecosystem together. Their removal resulted in a kelp forest overrun with urchins that had collapsed from rich habitat to deserts known as urchin barrens. Borrowing an architectural term, sea otters became one of the earliest animals to be designated a “keystone species.”

As sea otters continue to recolonize their pre-fur-trade range, their role in “new” habitats and locations becomes clearer. The relationship between predator and prey, herbivore and plant, plant and productivity may remain constant, but the cast of characters (the array of species) and the complexity inherent to each place changes the story.

Less than a decade ago, in an estuary at the heart of Monterey Bay, Dr. Brent Hughes discovered a trophic cascade that flowed from sea otter predation on crabs through to the tiniest of housekeepers that allow eelgrass beds to flourish. In Elkhorn Slough, Hughes found that sea otters’ preference for predatory crabs allowed the prey of the crabs, small grazers like sea slugs and isopods, to graze the surface of eelgrass beds clean of suffocating microalgae.

Today, all along the west coast of North America, another ecological collapse has wrought both devastation and an opportunity for study. The large-scale devastation of some key species due to sea star wasting syndrome has resulted in both predictable and unexpected ecological effects. The sudden loss of predators like the ochre star (Pisaster ochraceus) and the sunflower star (Pycnopodia helianthoides) has had a dramatic effect on the numbers of their prey, most notably mussels and urchins. Urchin barrens have spread along the California coast, even in some areas long inhabited by sea otters.

As a sea otter scientist in the wake of this ecological shift, I have often been asked, “If sea otters are really this keystone species, why aren’t they preventing urchin barrens within their Central California Coast range?” One study, funded by the National Science Foundation, is searching for the answer to that question.

A partnership of UC Santa Cruz, US Geological Survey, and the Monterey Bay Aquarium, the Monterey Predator Diversity Project, nicknamed the Otter-Star Project, is taking a multi-faceted look at the effects of predator diversity on the stability and resilience of kelp forest ecosystems in the face of this ongoing sea star epidemic. The cast of characters acting as predators in California’s kelp forests is much more diverse than Dr. Estes found in the Aleutians. Here, sea otters share the stage with urchin-eating fishes, wolf eels, lobsters, and (before the rise of the epidemic) sunflower stars—the food web here is a complex tangle of lines and arrows. Human-induced factors like pollution, overfishing, and climate change complicate the story further. Since 2016, the Otter-Star Project has been watching, testing, and analyzing as the ecological drama continues to unfold. As we await the results of this study, we will have to be content with the wonder of it all and the knowledge that the story is not yet concluded.

As they rebound from near extinction, sea otters have brought with them healthy, diverse, and more stable coastal ecosystems. Throughout their recovery, scientific study of their effect on habitats has increased our understanding not just of sea otters’ keystone role in kelp forests, but also of the importance of predators to many ecosystems. Scientists are just now beginning to understand the ecological role of sea otters in other imperiled coastal habitats like estuaries, and the complexity of their interactions within the diverse kelp forests of California.

At a time when we desperately need more sources of carbon-absorbing plant cover, the positive effect of sea otters on abundance of kelp and sea grass makes them part of a global team of predators helping to mitigate climate change. I doubt there is solace for the sea otter that it took such devastation to their numbers for humans to recognize and appreciate the part they play in keeping the coastline where we live, eat, and play, healthy.

That little girl from 1970 was heartened to see them at rest in the kelp beds of Pacific Grove, at rest as they had been long before the first humans stood on that spot. Today, I am just as heartened and inspired at the sight of them—so much more than just a pretty face.

Learn more

Must see video: Nature episode, “The Serengeti Rules,” includes a section on sea otters.

Related reading: Serendipity: An Ecologist’s Quest to Understand Nature, by Dr. James A. James Estes.

About Gena Bentall, Guest Author

Since 2001, Gena has worked as a sea otter biologist, studying sea otters in such wide ranging locations as the Aleutian Islands, Russia’s Commander Islands, San Nicolas Island off the coast of Southern California, and along the Central California coast. She studied zoology and marine biology at Oregon State University in Corvallis, and obtained her master’s degree in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of California Santa Cruz under Dr. James Estes. After years of studying sea otters in the wild, Gena has learned much about their unique biology and behavior, and witnessed first-hand the chronic nature of disturbance to sea otters by human recreation activities. Gena now coordinates the Sea Otter Savvy program and reaches out to the central coast communities of Monterey, San Luis Obispo, and Santa Cruz counties.

Subscribe to our weekly blog to have posts like this delivered to your inbox each week.

Help us protect and restore the Morro Bay estuary!

- Donate to the Estuary Program today and support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.

The Estuary Program is a 501(c)3 nonprofit. We depend on funding from grants and generous donors to continue our work. - Support us by purchasing estuary-themed gear from ESTERO. This locally owned and operated company donates 20% of proceeds from its Estuary clothing line and 100% of Estuary decal proceeds to the Estuary Program. Thank you, ESTERO!

- Purchase items from the the Estuary Program’s store on Zazzle. Zazzle prints and ships your items, and the Estuary Program receives 10% of the proceeds. Choose from mugs, hats, t-shirts, and even fanny packs (they’re back!) with our fun Estuary Octopus design, our classic Estuary Program logo, or our Mutts for the Bay logo.