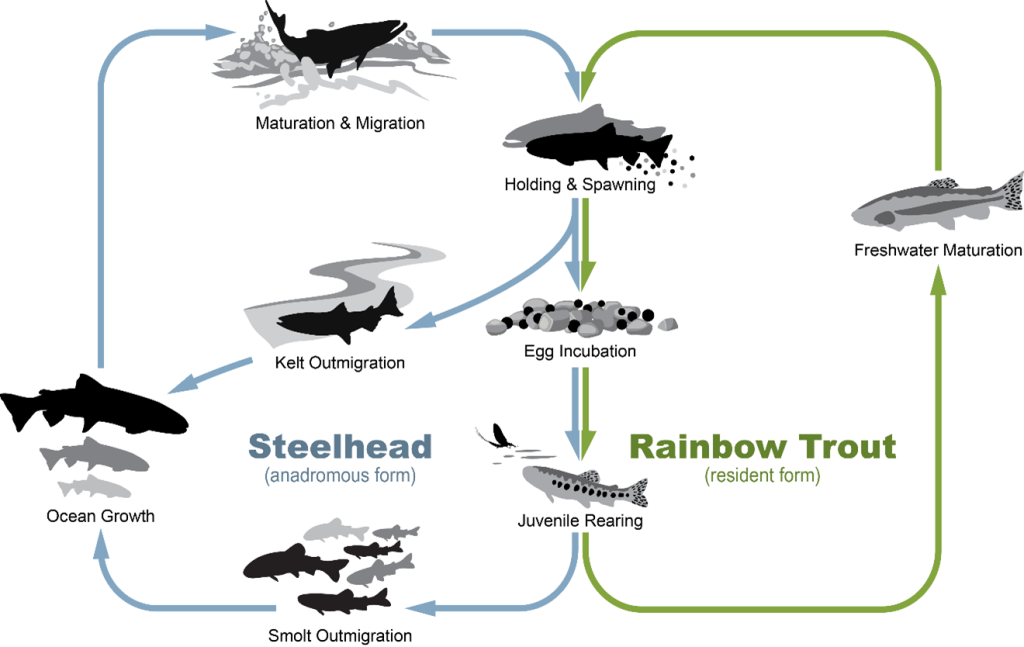

The Morro Bay watershed is home to a unique species called steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). These fish are born in freshwater streams like Chorro Creek. Some spend their entire lives in the creek and are known as resident rainbow trout. Others, known as steelhead, spend a few years in freshwater and estuary environments before journeying to the ocean. Whether a fish becomes a steelhead trout or remains a resident rainbow trout depends on genetic and environmental factors.

Steelhead require healthy creek, estuary, and ocean environments to support their life cycle. The Estuary Program works to protect creek habitat, water quantity, and water quality to benefit this threatened fish population. As part of an effort to better understand steelhead populations in the watershed, we recently embarked on a two-year steelhead growth and tracking study.

Understanding Migration and Movements

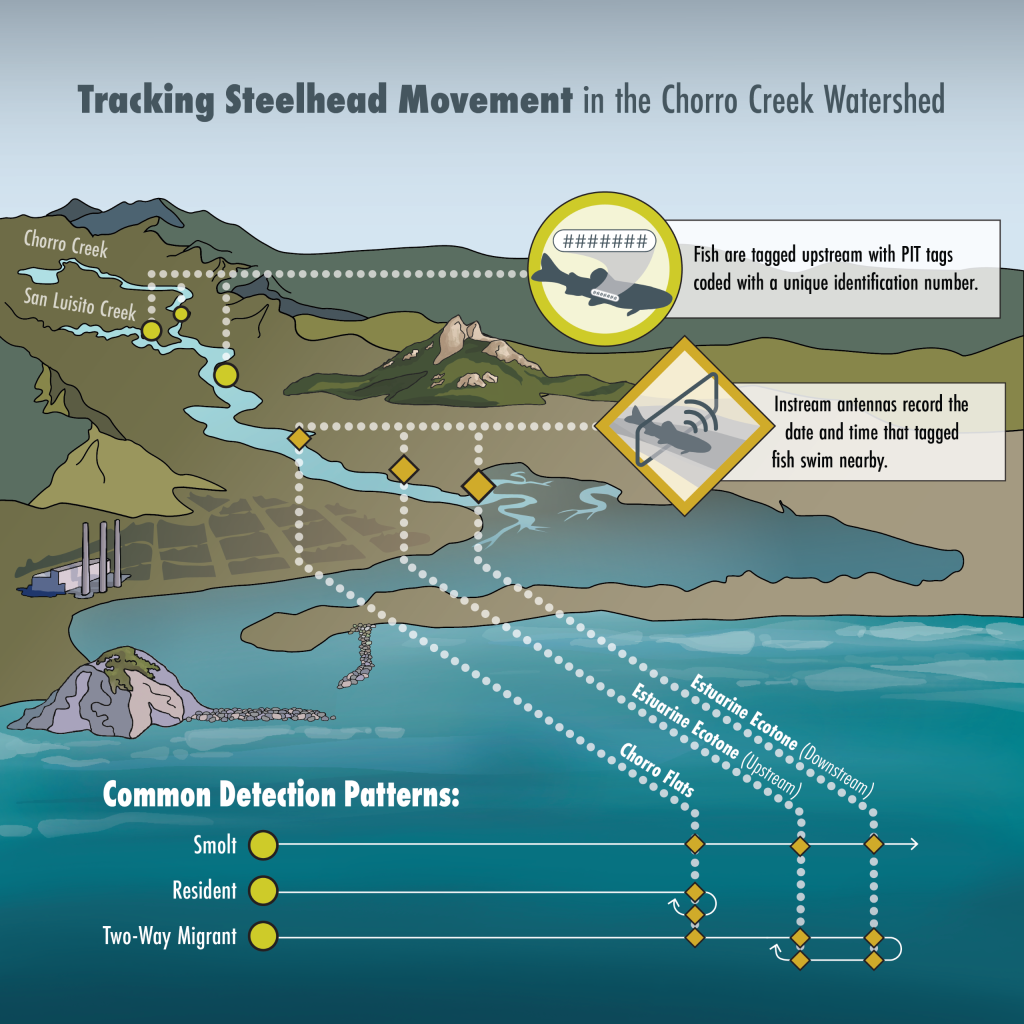

A key goal of this study was to determine how and when steelhead migrate between local creeks and the estuary. Understanding these patterns can help us identify times of year when fish need enough flowing water to migrate, which can lead to projects that protect surface water flows. It also tells us when to avoid certain activities that might interfere with fish movement. To answer these questions, we monitored the movement and growth of individual fish in Chorro Creek and San Luisito Creek, a smaller tributary that drains into it.

How Do You Track Fish Movement and Growth?

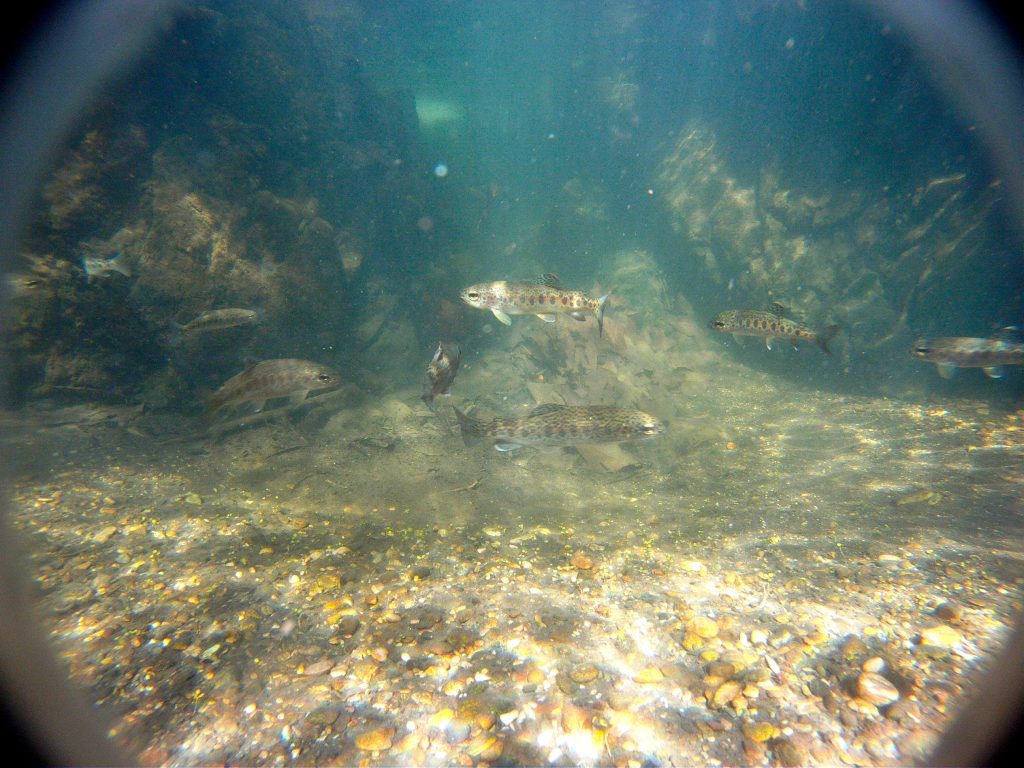

As you can imagine, tracking fast-moving, migratory fish can be tricky. For this study, we used a method called mark-recapture, where we implanted fish with a unique tag called a Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT), then recaptured them at a later date. To tag the fish, we used backpack electrofishers to temporarily stun and capture fish. We placed them in buckets with aerated creek water to keep them well-oxygenated, and then we counted and measured all fish.

We anesthetized steelhead that were of sufficient size, implanted PIT tags, and then released them back into the creek. PIT tags are essentially microchips similar to the type used to chip dogs and cats.

We conducted this work at 17 sites along Chorro Creek stretching from Chorro Flats to just below the Chorro Reservoir behind the California Men’s Colony. The work was also conducted on two sites on San Luisito Creek. This fish capture and tagging work took place in fall 2023, spring 2024, and fall 2024. If we recaptured the tagged fish during subsequent fieldwork, we would again weigh and measure them to calculate their growth rate.

Once the tags are implanted, you need a way to track them as they move through the creeks. We installed stationary PIT-tag antennae in lower Chorro Creek, one just downstream of the South Bay Boulevard Bridge within the estuarine ecotone (transition zone from fresh to salt water) and one in Chorro Flats (near Quintana Road). As fish pass by an antenna, a reader scans the microchip in the tag to record a fish’s unique identifier.

What Did We Learn?

The data revealed interesting differences in fish density between creeks. In Chorro Creek, the density ranged from 4 to 102 fish per 100 meters of creek, whereas in San Luisito Creek it ranged from 44 to 263 fish per 100 meters of creek. As we collected limited data in San Luisito Creek, it’s not clear whether this higher density is a consistent trend until more data is collected.

We captured a total of 1,225 steelhead, and approximately 70% of them were large enough to PIT tag. Of the tagged fish, 7% were recaptured at least once, with only a handful recaptured at least twice. Juvenile fish (aged 0+) captured in Chorro Creek tended to have higher growth rates than those in San Luisito Creek. This is likely due to fewer fish present and warmer stream temperatures in Chorro Creek. There was no difference in growth rates for fish aged 1 to age 2+ between the two creeks. The higher density of juvenile fish on San Luisito Creek likely contributed to lower growth rates as there were more fish competing for habitat and food.

The data also provided information on fish movement. A total of 201 fish were detected at the antennae between 2023 and 2025. Of these:

- 57% were detected only in the Chorro Flats area and are likely resident rainbow trout who will spend their entire lifespan in fresh water.

- 6% were considered to be one-way migrants from the creek to the ocean because they were originally tagged at an upstream location.

- 37% were detected at the estuarine ecotone antennae. Of these, 90% were one-way migrants, or smolts, that did not return after passing over the estuarine ecotone antennae, while the remainder were considered two-way migrants as they were later detected upstream at Chorro Flats.

The typical pattern of fish movement was for age 2+ fish to migrate from higher up in the creeks to down past Chorro Flats, and then a few days later to continue downstream past the estuarine ecotone antennae. A few fish spent more time near the estuarine ecotone antennae and were detected in that location many times over several weeks. Based on fish movement, the window for smolting (transitioning from freshwater to saltwater habitat) in the Chorro Creek watershed was roughly January to April, but the start is typically dependent on a large rain event.

What’s Next?

This study provided fascinating new information on this iconic species. Next, we want to learn more about the role of the tributaries for steelhead trout in the watershed. We hope to undertake tagging work in San Bernardo, Pennington, and Dairy Creeks in the future.

Help us protect and restore the Morro Bay estuary!

- Donate to the Estuary Program today and support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.

The Estuary Program is a 501(c)3 nonprofit. We depend on funding from grants and generous donors to continue our work. - Support us by purchasing estuary-themed gear from ESTERO. This locally owned and operated company donates 20% of proceeds from its Estuary clothing line and 100% of Estuary decal proceeds to the Estuary Program. Thank you, ESTERO!

- Purchase items from the Estuary Program’s store on Zazzle. Zazzle prints and ships your items, and the Estuary Program receives 10% of the proceeds.

- Subscribe to our seasonal newsletter: Between the Tides!

- We want to hear from you! Please take a few minutes to fill out this short survey about what type of events you’d like to see from the Estuary Program. We appreciate your input!