This past week, our Executive Director and Communications & Outreach Coordinator Rachel Pass journeyed all the way to New Orleans, Louisiana. There, they met with staff from the 27 other National Estuary Programs across the country and toured the local Barataria-Terrebonne estuary.

National connections

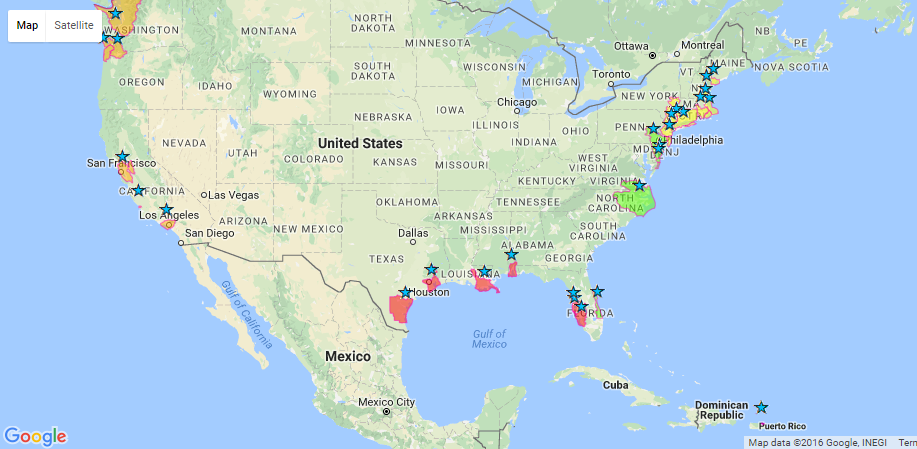

Congress established the National Estuary Program in 1987 through the Clean Water Act. There are currently 28 estuaries in the country included in the non-regulatory program. Each of these estuary programs works to address critical water quality issues in their area.

National Estuary Programs protect bays big and small. Puget Sound, San Francisco Bay, and the New York/New Jersey Harbor are included, as is the much smaller San Juan Bay in Puerto Rico. Morro Bay is the second smallest estuary of national significance. (More than 400 Morro Bays could fit inside San Francisco Bay!) Over the past 10 years, these programs have protected and restored more than 1 million acres of estuary habitat.

President Barack Obama reauthorized the National Estuary Program in spring of 2016. This helps protect the 42% of the continental U.S. shoreline covered by the National Estuary Programs.

How did Morro Bay get national recognition?

Though it is small, Morro Bay is very important to people and wildlife alike. It is one of the best-preserved estuaries in central and southern California. It’s an important bird area and an essential stop on the Pacific Flyway, a shelter for juvenile fish, a habitat for diverse wildlife and plants, and a huge economic and recreational resource for the community.

Thousands of concerned citizens came together to preserve Morro Bay in the 1980s, when it was discovered that it was filling in at an unnatural rate. They formed the Friends of the Estuary and the Bay Foundation, among other groups. Through the tireless efforts of these champions of the bay as well as many agency and organization partners, Morro Bay achieved recognition at the state level in 1994 and was accepted as a National Estuary Program in 1995.

Bill Newman, one of the founders of the Morro Bay National Estuary Program, discusses how it all began.

National Estuary Programs come together

Though each National Estuary Program is an independent organization, they all deal with similar issues. Two annual meetings bring staff from all 28 National Estuary Programs to come together and discuss the challenges their estuaries face as well as methods for addressing them. These meetings allow us to learn from one another and to see the similarities and differences between the places we protect.

Issues facing Barataria-Terrebone Estuary

Visiting the Barataria-Terrebonne estuary outside of New Orleans gave our staff a new perspective. While the Morro Bay estuary is filling in too quickly, the marsh lands that make up this large estuary at the mouth of the Mississippi are quickly losing ground. More than one football-field of land is lost each hour in coastal Louisiana.

This is due in part to the fact that the river is extensively leveed in order to control flooding during storms, and to keep industry moving upstream and down. These levees protect people and businesses, but they also keep water and sediment from flowing into the marshes and deltas, which would allow them to continue to build up. Without the input of new sediment, waves and strong currents wash the land away. The rate of land loss has increased with sea level rise and climate change, which has increased the number and size of storms. Learn more about erosion and land loss in Louisiana.

Work to address the land loss problem

The Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program and their partners are doing great work to combat this problem. Some of their large-scale projects have involved adding walled or fenced areas along shorelines. These barriers slow wave action, keeping existing land masses intact and allowing some sediment to build up behind them, creating new marsh land between the barriers and the current shoreline.

Through a tour put together by Restore America’s Estuaries, we also had the chance to tour an oyster shell recycling project run by the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana in Plaquemines Parish, one of the areas on the frontline of the erosion problem.

Oyster shells are collected from restaurants throughout New Orleans and assembled in large piles to cure in the open air for six months or more. This ensures that the shells won’t introduce anything harmful to the bay. Volunteers pack the cured shells into bags, and contractors assemble them into artificial reefs in intertidal areas.

These reefs slow waves, allow sediment to build up behind them, and provide valuable habitat for new oyster populations to grow. The first artificial oyster reef went into action at the beginning of December, and we’re excited to see how it works to help preserve and protect this important stretch of estuarine coastline across the country from Morro Bay.