The Morro Bay National Estuary Program’s fieldwork has been deemed an essential service by the County of San Luis Obispo. Due to COVID-19 safety precautions, we are not working with volunteers at this time and our field staff are following updated monitoring protocols. We look forward to working with volunteers and other community members again as soon as it is safe for us to do so. Thank you, readers, for staying engaged and supporting the Estuary Program’s work during this difficult time.

What’s Living in the Eelgrass?

Estuary Program staff have continued to monitor eelgrass into January 2021, following a series of extremely low tides this past month. Low tides like these expose eelgrass, making it easiest to monitor effectively and efficiently.

While monitoring efforts are focused on assessing eelgrass density, staff often stumble upon eelgrass-dwelling critters while in the field. This month, our staff found a few interesting invertebrates to report back on:

1. San Diego Dorid (Diaulula sandiegensis)

The San Diego dorid (Diaulula sandiegensis), also known as the leopard dorid or ring-spotted dorid is an intertidal nudibranch, found along the west coast of North America as well as Japan. This shell-less gastropod can be easily identified by its brown, leopard-like spots. Diaulula sandiegensis’ diet chiefly consists of sponges.

The Estuary Program spotted two San Diego dorids during January eelgrass monitoring. Each dorid was approximately three to four inches in length and found taking refuge in dense eelgrass beds, as seen in the photo above.

2. Hooded Nudibranch (Melibe leonine)

This video shows a lion’s mane nudibranch in the eelgrass in Morro Bay.

The Melibe leonine is a translucent nudibranch, called a variety of common names including hooded nudibranch, lion’s mane nudibranch, or simply, lion nudibranch. All of these common names refer to its distinct oral hood, which allows the nudibranch to capture its prey.

Two hooded nudibranch were found during January eelgrass monitoring. These nudibranch were slightly smaller than the dorids, at about two to three inches in length.

Click here to check out another cool video of M. leonine in motion from the Monterey Bay Aquarium!

3. Lesser Two-Spot Octopus (Octopus bimaculoides)

Estuary Program staff found one juvenile Two-Spot Octopus (Octopus bimaculoides) during eelgrass monitoring near Morro Rock. This tiny inklet, only about two inches in size, has an uncertain future. Given its washed up location and lack of activity, it’s likely that this octopus is experiencing senescence, a natural process and the precursor to death. Two-Spot Octopus are not known to live particularly long lives, generally only making it to twelve to eighteen months of age. Like salmon, octopus only mate once and die shortly after spawning.

Monitoring Rainfall and Flow

Rain, rain, please don’t go away!

San Luis Obispo County received a substantial amount of much-needed rainfall during late January. Between January 26th and January 29th, the San Luis Obispo County rain gauge at Canet Road measured 7.8 inches of rainfall, making it the largest rain event during water year 2021 so far. This storm has accounted for nearly 77% of the accumulated rainfall for this water year, which has a running total of 10.1 inches, as of February 1st.

How does this year’s rainfall stack up with other years? Let’s take a look…

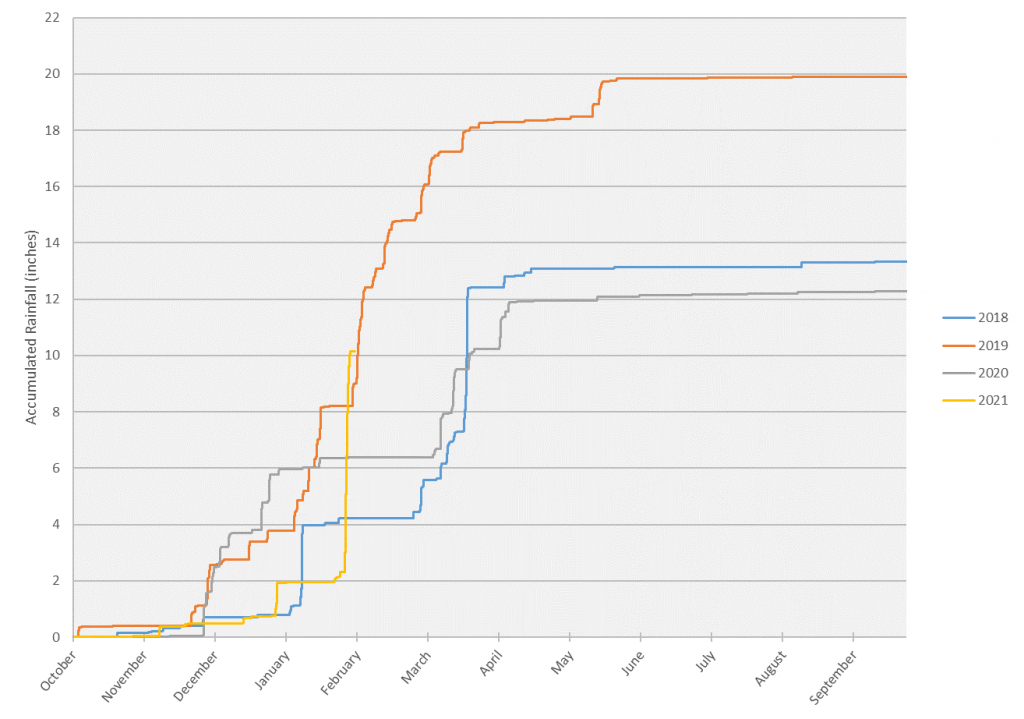

The graph above shows rainfall accumulation over the course of each water year (October 1st to September 30th), from water year 2018 to water year 2021. Each time there is a vertical rise on the colored lines, this indicates more rainfall. We can visualize large storm events with drastic vertical rises, and dry periods with horizontal plateaus.

When comparing the vertical rises on the graph above, it’s apparent that water year 2021 (the yellow line) has had the most drastic vertical rise of the last four years. We can see that water year 2018 (the blue line) had a substantial mid-March storm, but not quite at the same magnitude of this year’s storm.

Rainfall events with this kind of intensity have the capacity to create major flow events. In fact, when comparing this year’s peak flow (the maximum recorded stream discharge in cubic feet per second), water year 2021 has had the seventh highest peak flow in the last forty years.

This major peak flow event caused the bridge at Canet Road to overtop and flooded multiple other local roads. The time series photo below shows the progression of the storm at Canet Road, between January 26th and 28th, 2021.

Our fingers are crossed here for a wet February and a Miracle March!

Interested in hearing more? You can stay up to date with all things fieldwork related by subscribing to our blog. We put out weekly posts and field updates on the first Friday of every month. Subscribe here to never miss a post!

Help protect and restore the Morro Bay estuary

- Donate to the Estuary Program and support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.

The Estuary Program is a 501(c)3 nonprofit. We depend on funding from grants and generous donors to continue our work. - Support us by purchasing estuary-themed gear from ESTERO. This locally owned and operated company donates 20% of proceeds from its Estuary clothing line and 100% of Estuary decal proceeds to the Estuary Program. Thank you, ESTERO!

- Purchase items from the the Estuary Program’s store on Zazzle. Zazzle prints and ships your items, and the Estuary Program receives 10% of the proceeds. Choose from mugs, hats, t-shirts, and even fanny packs (they’re back!) with our fun Estuary Octopus design or our Mutts for the Bay logo.