Why does the water look red?

Have you noticed dark, murky water in or around Morro Bay recently?

According to Dr. Ryan K. Walter from Cal Poly, samples retrieved from the Cal Poly pier as well as those collected near the mouth of Morro Bay at Morro Rock have shown abnormally high concentrations of a single-celled phytoplankton dinoflagellate called Akashiwo sanguinea during the month of August.

Blooms of phytoplankton like the ones observed from Cal Poly can accumulate to form what is known as a red tide, resulting in murky, often red-appearing water. Red tides are blooms of phytoplankton, which occur seasonally and are typically non-toxic. Red tides like this are somewhat normal for this time of year as phytoplankton tend to thrive in warmer, calmer waters, often accompanied with elevated levels of nutrients.

Red tides can persist for weeks or even months, depending on conditions. In Morro Bay, the increase in phytoplankton A. sanguinea concentration was first observed around mid-July, lasting until early August. During August, concentrations dropped and then picked back up again toward the end of the month.

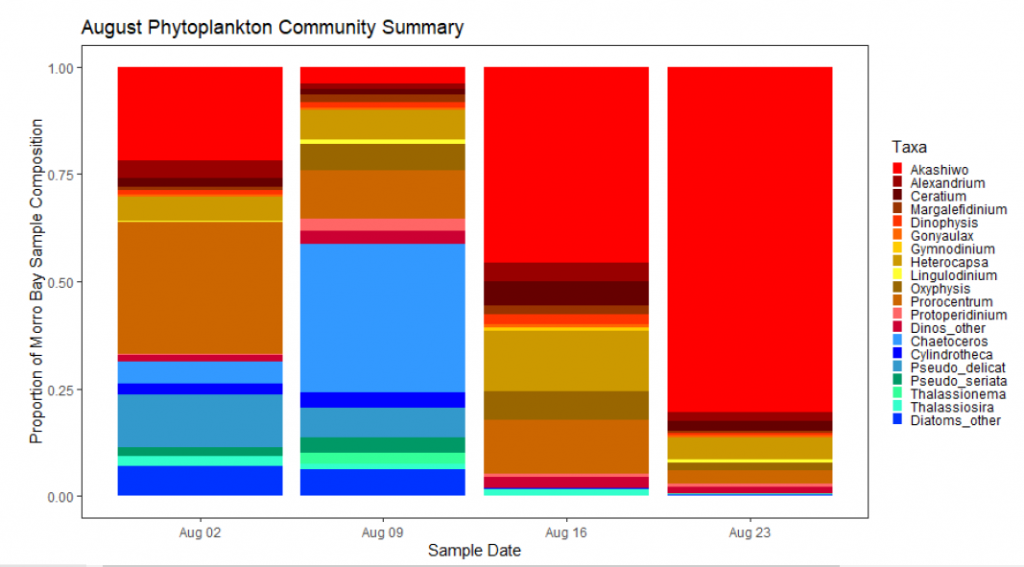

The graph above, provided by former Cal Poly undergraduate, Nicholas Soares, visualizes the relative concentrations of phytoplankton in Morro Bay during August, showing how concentrations of different taxa have varied throughout the month, as. In the graph, the A. sanguinea taxa is indicated by the bright red color at the top of each bar, while the other shades and colors represent different phytoplankton taxa. The wider bars indicate higher species composition, while the narrow bars indicate a lower composition.

In early August, A. sanguinea accounted for nearly one-quarter of the phytoplankton sampled. By August 9th, this changed to a much smaller fraction of the sample, but then rebounded by the 23rd, where A. sanguinea made up nearly three-quarters of the phytoplankton sampled.

Phytoplankton samples collected by Cal Poly are made possible through funding contributed by the Southern California Coastal Ocean Observing System and the hard work of students like Nicholas Soares and Elysa Romanini.

Toxic phytoplankton

The phytoplankton thought to be most contributing for the recent red tide in Morro Bay, A. sanguinea is not known to be toxic for humans. Other types of phytoplankton though, like the dinoflagellate Alexandrium produces paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) toxins, which are among the most potent natural toxins known to date.

Thankfully, the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) keeps a close eye on toxic phytoplankton, through the use of a volunteer-based phytoplankton monitoring program which routinely samples for toxic phytoplankton along the entire California coastline.

Results from the monitoring program can be visualized on their interactive phytoplankton map, or from their monthly reports.

Implications for wildlife

While the recent bloom of A. sanguinea is not believed to be toxic for humans, the implications for wildlife could be more severe, depending on the intensity and concentration of the bloom.

In 2007, over 750 seabirds washed up to along the coast of Monterey, CA. At this time, it was unclear exact the culprit of the die-off as scientists had never documented an occurrence like it before. Ultimately, research indicated that the cause of the mass seabird stranding was a substantial bloom of A. sanguinea. Nearly one-quarter of the birds died as a product of the bloom.

In January of 2019, another bloom of A. sanguinea along the coast of Oregon and Washington led to one of the largest single mortality events of seabirds on the West Coast, killing over one thousand birds including scoters, common murres, common loons, red-throated loons and grebes.

While blooms of A. sanguinea can be associated with seabird die-off, the implications are not direct. Red tides and similar blooms of A. sanguinea have and do occur without detrimental impacts to wildlife. Toxins produced from the bloom may be amplified by other factors like weather and large waves, which could exacerbate its effects as seen in 2007.

Volunteering at the Estuary Program

Due to the continued uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Estuary Program has chosen to take a step back from recruiting new volunteers for the fall. Those interested in volunteering with the Estuary Program should reach out toward the latter end of the calendar year, as we begin to recruit volunteers in January for spring 2022 bioassessment.

In the meantime, be sure to stay tuned for next month’s field updates post, by subscribing to our blog.

Subscribe to our blog

Get it delivered to your inbox by subscribing today.

Help protect and restore the Morro Bay estuary

- Donate to the Estuary Program and support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.

The Estuary Program is a 501(c)3 nonprofit. We depend on funding from grants and generous donors to continue our work. - Purchase estuary-themed gear from ESTERO. This locally owned and operated company donates 20% of proceeds from its Estuary clothing line and 100% of Estuary decal proceeds to the Estuary Program. Shop online at esterosurf.com or at Joe’s Surfboard Shop in Morro Bay. Thank you, ESTERO!

- Purchase items from the the Estuary Program’s store on Zazzle. Zazzle prints and ships your items, and the Estuary Program receives 10% of the proceeds. Choose from mugs, hats, t-shirts, and even fanny packs (they’re back!) with our fun Estuary Octopus design or our Mutts for the Bay logo.