When you think about sharks, what comes to mind? Chances are, you’ll picture a tall, angular fin cutting through the waves and rows upon rows of sharp teeth. You might even picture a shark attack from the movies, with people fleeing up the beach and away from the waterline.

It’s less likely that you’ll picture one of the three sharks that thrive in Morro Bay’s protected waters, the swell shark, leopard shark, and horn shark. These diminutive sharks are not the stuff of horror movies, unless you’re a small fish, clam, innkeeper worm, crab, or any of the other mollusks and crustaceans that these bottom-feeders feast on. In their own habitat, including the sandy bottom of Morro Bay, these sharks are at the top of the food chain.

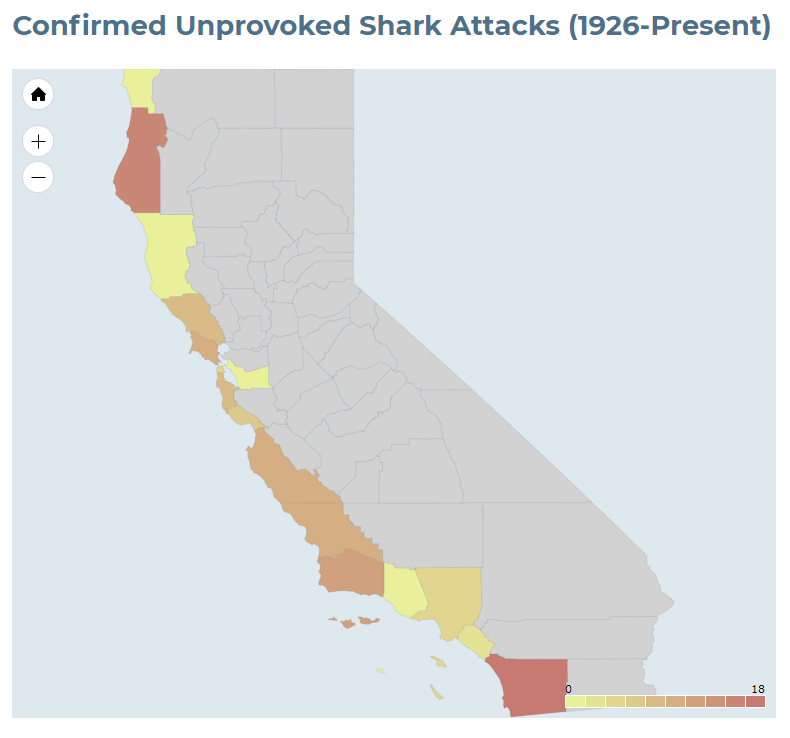

It is true that sharks are fierce predators, but humans are very unlikely to be their chosen prey. In fact, studies show that people are thirty times more likely to be killed by lightning than by a shark, according to the International Shark Attach File (ISAF). The map below, created by ISAF, shows the numbers of unprovoked shark attacks per county since 1926. San Luis Obispo County falls in the middle of the range with a total of 11 shark attacks. For more specific information about shark attack locations across California’s coast, you can visit the Shark Research Committee for a list of shark attacks between 2000 and the present.

Though the Los Angeles Times reports that West Coast saw five more shark attacks in 2017 than in 2016, it remains to be seen whether or not these numbers will track with the growing population of white sharks off California’s coast. This is one of the questions Assembly Bill 2191, which would establish the White Shark Population Monitoring and Beach Safety Program, seeks to answer. The bill is made its way though the California State Legislature, was approved as part of California’s budget on June 15, and is now on its way to the Governor’s desk. If it is signed, it will fund shark research, including tagging and monitoring programs, and may also provide funding for lifeguards and beach safety programs.

People’s fear of sharks is understandable; these large, toothy, carnivorous fish have been around for human’s entire evolutionary history. (Scientists have found fossils of shark scales from 450 million years ago, and shark teeth from 400 million years ago.) Avoiding contact with them has, likely, always been a wise decision.

Despite this, sharks, as apex predators, are an indispensable part of the food web. The fact that there are more sharks may indicate the success of conservation efforts, which are allowing them to return and, in their turn, to provide balance to marine ecosystems.

So, in honor of sharks, we invite you to celebrate the 30th annual Shark Week by participating in some citizen science instead of (or in addition to) watching Jaws. Here are some citizen science projects that you can contribute to from Central Coast and beyond.

- The Shark Trust: Great Eggcase Hunt: asks citizen scientists to find and enter location information for empty shark eggcases (often called mermaid’s purses) around the world.

- SharkBase: asks you to enter your past and present shark sightings. You can even enter information from local newspapers, social media, and news programs on television.

- eShark: Do you SCUBA dive? If you do, log your ocean dives—even if you don’t see a shark—to help scientists track shark and ray populations.

For more posts like this one, subscribe to the Estuary Program blog.

Donate to the Estuary Program to support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.

You can also support us by purchasing estuary-themed gear from ESTERO or from our Estuary Program store!