Steelhead in the Morro Bay Watershed

One of the fascinating creatures living in our local creeks is the South Central California Coast Steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss). This genetically-distinct population of steelhead is found exclusively from the Pajaro River to the Santa Maria River, and while historically abundant, they were listed as “Threatened” by the National Marine Fisheries Service in 1997 due to rapidly declining numbers. This species continues to struggle due to habitat loss, lack of water, and competition with invasive species.

Steelhead belong to the Salmonidae family, along with other species of trout and salmon. Steelhead are anadromous, meaning they are born in freshwater streams, migrate out to sea for several years, and then return to freshwater to spawn. While the ability to make the transition from freshwater to saltwater is an impressive feat, steelhead are still very sensitive to water quality. They require cool, clean, well-oxygenated water to survive and reproduce.

Monitoring Creek Temperatures

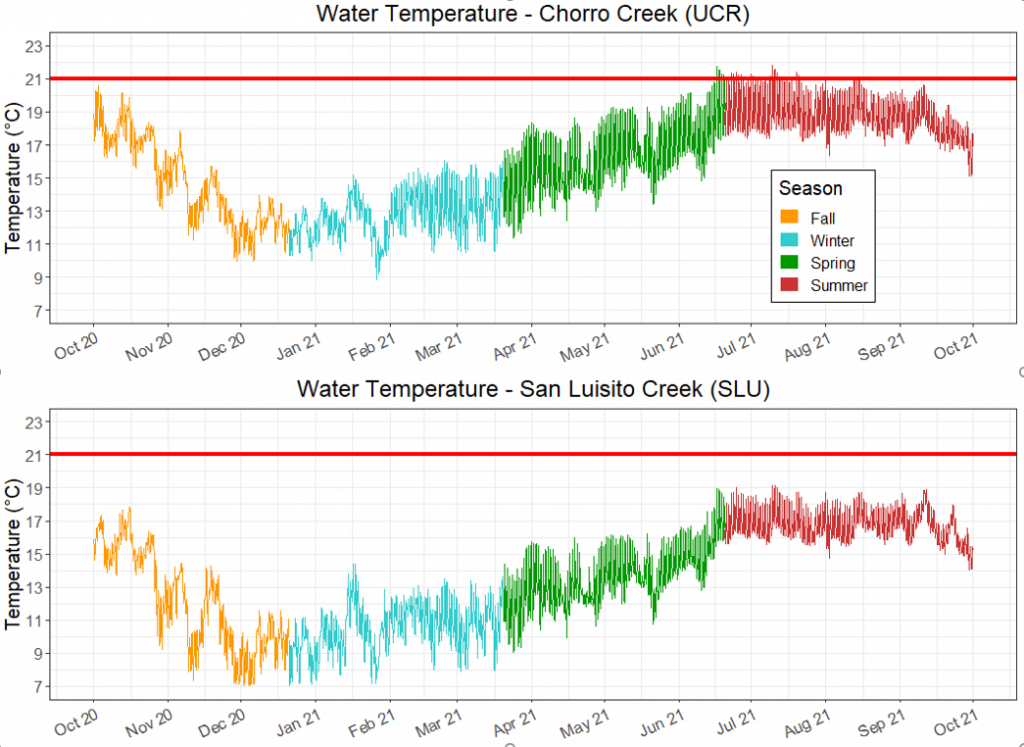

For steelhead, extended periods of time spent in waters warmer than 21°C pose a significant threat to their survival. Warmer waters can negatively impact their reproduction, growth, migration timing, and stress levels. However, it’s important to keep in mind that the 21°C threshold is a level these fish need to survive, and they really need cooler waters in order to thrive. Since water temperature plays a major role in determining how hospitable a creek is for steelhead, the Estuary Program maintains a network of six temperature sensors.

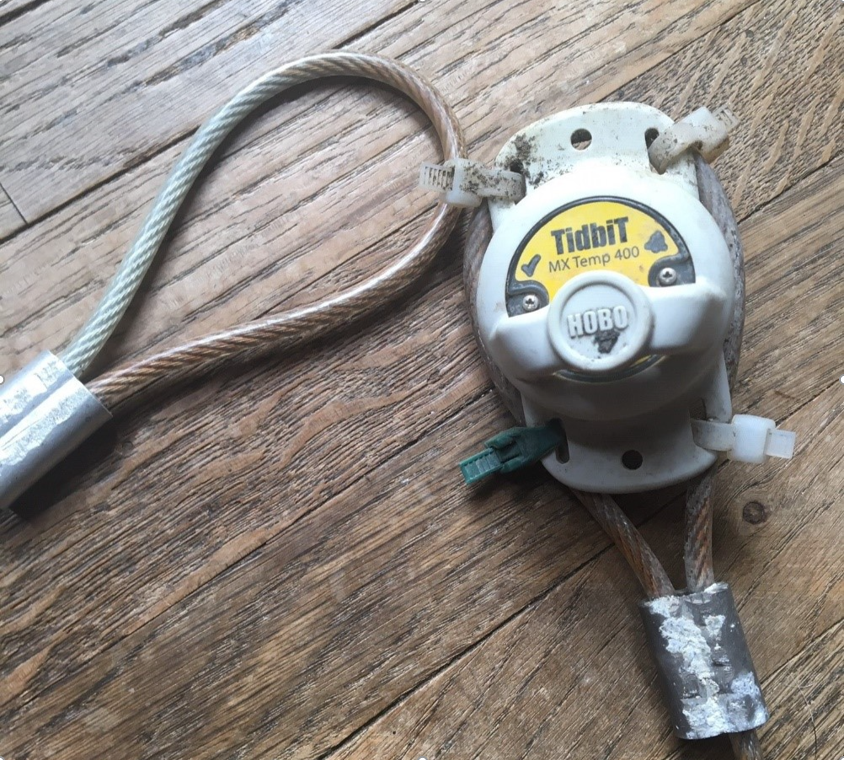

These temperature loggers are called “TidbiTs,” and they are especially useful because they are compact, durable, and have a battery life that can last up to five years. Measuring water temperature every half hour creates a valuable data set since it allows us to see how often and for how long waters may be warmer than ideal for steelhead.

While steelhead also require well-oxygenated waters, measuring dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration is a bit trickier and more expensive. Luckily temperature can be used as a reliable proxy for DO since colder waters usually mean higher oxygen levels and warmer waters mean lower oxygen levels. The Estuary Program also uses a DO probe to collect measurements during our monthly site visits to ensure accuracy.

The graphs above show how temperatures differ between the mainstem of Chorro Creek (top graph) and one of its tributaries (bottom graph). The tributaries typically remain colder than the mainstem year-round, and don’t go above the 21°C threshold during the summer months. The tributaries may require a longer swim to access than the mainstem, but their cooler waters provide excellent habitat for steelhead.

Overcoming Obstacles

To complete its life cycle, steelhead must be able to migrate unimpeded from the ocean to the creeks and back. Typically, between late January and May, adult steelhead return to the creeks in an attempt to find a nice patch of gravel to spawn and large wood pieces for shelter. While some scattered wood is helpful, impassible barriers abruptly cut their journey short, forcing them to settle for less-than-ideal habitat which may negatively impact the survival of their eggs. The chance of survival for juveniles is improved if they have more creek habitat to access, allowing them to find food, resources, and hide from predators. To help improve habitat for steelhead, the Estuary Program is currently working with partners to assess removal of two barriers on San Luisito Creek.

Creek connectivity is not only important for major seasonal migrations but also for the day-to-day movements that allow fish to take advantage of resources in different creek segments. A recent study from the Santa Cruz area described how steelhead move upstream and downstream throughout the day in response to foraging opportunities and predation risk. When creeks are disconnected due to low flow rates or barriers, the steelhead may have a harder time finding food and an easier time becoming something else’s food.

In addition to barriers, invasive fish lurking in the creeks compound the difficulty of a steelhead’s trek upstream. The Sacramento pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus grandis) is an unwelcome visitor to the Morro Bay watershed because it feeds on juvenile steelhead and competes for resources. The Estuary Program and Stillwater Sciences are actively involved in managing pikeminnow to protect steelhead populations. An upcoming blog post will share the latest results from this effort.

It’s definitely not easy being a steelhead, but the Estuary Program is committed to using a variety of strategies to restore the population and increase their rate of survival. As our efforts continue, we hope to see these fascinating fish become numerous in our creeks once again!

References

Bond, Rosealea M., Joseph D. Kiernan, Ann-Marie K. Osterback, Cynthia H. Kern, Alexander E. Hay, Joshua M. Meko, Miles E. Daniels, and Jeffrey M. Perez. “Spatiotemporal Variability in Environmental Conditions Influences the Performance and Behavior of Juvenile Steelhead in a Coastal California Lagoon.” Estuaries and Coasts, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-021-01019-9.

Subscribe to our weekly blog to have posts like this delivered to your inbox each week.

Help us protect and restore the Morro Bay estuary!

-

- Donate to the Estuary Program today and support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.

The Estuary Program is a 501(c)3 nonprofit. We depend on funding from grants and generous donors to continue our work. - Support us by purchasing estuary-themed gear from ESTERO. This locally owned and operated company donates 20% of proceeds from its Estuary clothing line and 100% of Estuary decal proceeds to the Estuary Program. Thank you, ESTERO!

- Purchase items from the the Estuary Program’s store on Zazzle. Zazzle prints and ships your items, and the Estuary Program receives 10% of the proceeds. Choose from mugs, hats, t-shirts, and even fanny packs (they’re back!) with our fun Estuary Octopus design, our classic Estuary Program logo, or our Mutts for the Bay logo.

- Donate to the Estuary Program today and support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.